by Kaori Shoji

Suicides in Japan are like wildfires in California: tragic, inevitable and seemingly unsolvable. According to the National Police Agency, 1805 people killed themselves in September and suicides amongst women were disproportionately rising.

Still, cases of people offing themselves had gone down in the past 10 years, and 2019 closed out the year with 20,169 cases – the lowest number of deaths since 1978 when the government first started keeping records, and minus 10,000-plus cases during the early naughts. Strangely enough, though the Japanese government is secretive and reticent about almost every other glitch found in the archipelago, they’ve always been upfront about the nation’s suicide rate. Few countries in the world are so ready to reveal the numbers but not in Japan.

Suicide has never been taboo here. Back when Tokyo was called Edo and the nation was closed off to foreigners, the suicide rate in this city was said to be twice what it is now, among a population of a mere one million, which is one-fourteenth of what it is today.

There was a collective mentality that dying by one’s own hand is the best and most effective way to make a statement or erase problems, and the legacy still holds.

Popular belief has it that every Japanese person goes through life knowing at least one person who committed suicide. (I myself have known six, but that’s fairly common.)

This year, suicides were low until June, but from July to August, the figures kept climbing. This was more or less in the cards – some experts had predicted as early as March that under the Covid-19 pandemic, more people will kill themselves than be killed by the virus. In August alone, 1854 people took their own lives of which 119 were women under 30 years old. This figure is alarming, but mainstream media seems too distracted to shed much light on why this is happening. Those who bothered however, tracked down Dr. Toshihiko Matsumoto, a psychiatrist who works almost exclusively with suicidal patients. According to Matsumoto, there had been an increase in young women with suicidal tendencies since Golden Week (early May), and those who couldn’t make it through the spring drove themselves over the edge during the summer.

Matsumoto said that in Japan, women commit suicides for different reasons from men. “Men’s problems almost always stem from work or the workplace, whereas women are much more social and are apt to encounter snags in their personal relationships. In pre-pandemic days girls could meet their friends for coffee, and just vent. But they were deprived of this pastime during the stay-home period. When the only people you see are family, there’s a lot of material for depression.” He has a point. Most Japanese daughters are diligent and dutiful, but they’re not ready to discuss life problems with mom and dad. “They don’t want to let their parents down,” explained Matsumoto, a logic that in itself is a breeding ground for suicidal thoughts.

Another factor triggering the suicides of young women could be the recent wave of self-inflicted deaths among actors/performers. These were celebrities who seemingly had everything to live for, and still chose death as a way out. In late May, professional wrestler Hana Kimura (22) was found dead in her home after being plagued by social media bullying. In July, the body of Haruma Miura (30) – one of the most popular actors in the industry, was found in his kitchen. After Miura came the death of actress and model Sei Ashina (36). The most recent shocker is the death of Yuko Takeuchi (40), an A-list actress whose career spans 25 years, and who had just remarried a co-star in February. There are five deaths so far, and only one of them left a note – actor Takashi Fujiki (80), whose body was found in a cheap, tiny apartment in Nakano ward.

Media analysts have mostly steered clear of the topic, fearful of stepping on the landmines strewn about on social media. Even a polite statement may be construed as offensive, hurtful or most damning of all – inspire others to die by their own hand.

Misako Noguchi, who has worked as a casting director for the past 30 years, says that she has never seen anything like it. “No matter how bad things got in the real world, it was very rare for performers to die of their own accord. The repercussions of something like that on the larger society would be enormous, and most stars were aware of that.” Noguchi says she blames Covid-19 – “when a performer is forced to stay home for weeks and months on end, it takes a huge toll on their mental health. I myself was going crazy, trapped inside the four walls of my apartment, broke and depressed. Imagine how a big star like Yuko Takeuchi would feel. She was used to being under the spotlight 12 hours a day, surrounded by cameras and people. Then suddenly, bang! Work dried up. She couldn’t even go outside.”

At this point, most Japanese have struck a deal with Covid-19. We’ll wear masks, disinfect vigorously and try to avoid crowds. Just please let us return to a semblance of normalcy. But for some Japanese, it may be too little, too late. Now mental health professionals fear that suicide rate will soar again in December – traditionally a month when many Japanese seek escape from year-end financial troubles by taking their own lives. Unemployment and failed businesses could push more people over the edge, and unlike the summer months, the deaths are expected to occur among people in their 40s to 60s.

It seems mind-numbingly strange that in a country famed for longevity and its super-aged society, suicides should be a leading cause of death. As Dr. Matsumoto says, “maybe what this society needs now isn’t protection measures but far less social distancing and more non-essential excursions.”

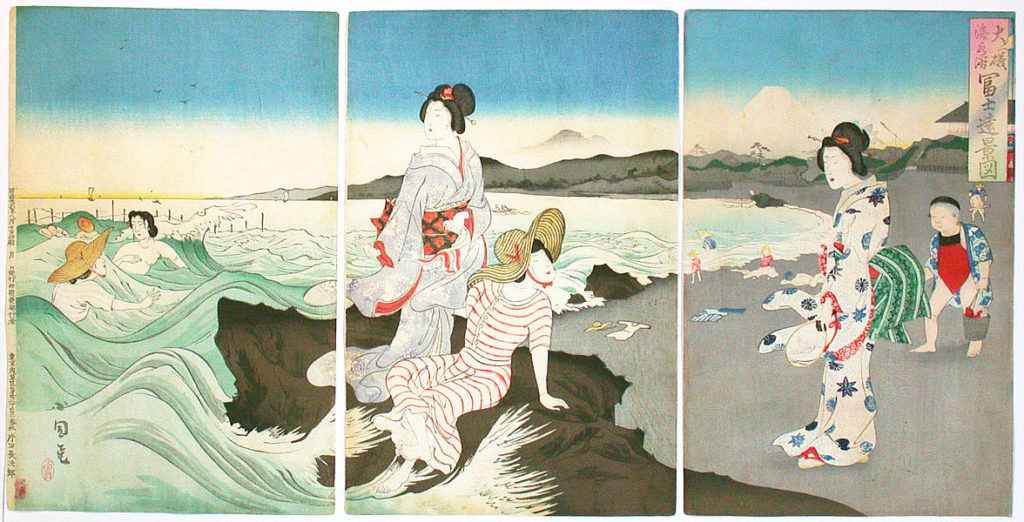

Artist:Utagawa Kokunimasa

Title:Beach Party (1893)

*****

If you’re considering suicide or know someone who is, this site in Japanese offers a number of ways to get counseling.

https://www.mhlw.go.jp/mamorouyokokoro/

In case of an emergency, please call 119 in Japan for immediate assistance. The TELL Lifeline is available in English for those who need free and anonymous counseling at 03-5774-0992. You can also visit them at telljp.com. For those in other countries, visit www.suicide.org/international-suicide-hotlines.html

[…] The number of people suiciding in Japan has plummeted in recent years, falling each year for the last decade. Last year there were 20,169 cases, the lowest number since 1978 when the government first started keeping records, and at least 10,000 fewer deaths per annum than during the early naughts. Japan Subculture […]