Richard Orange, noted foreign correspondent and Ikuru Kuwajima, a photojournalist in Central Asia and long-time contributor to Japan Subculture Research Center, worked to put together this this fascinating piece about one Japanese POW trapped in the Soviet Union after the end of the Second World War. It differs slightly from our usual subject matter but it’s a fascinating story that we hope you’ll enjoy. ●Marina Gorobevskaya also greatly contributed to this article.

By Richard Orange and Ikuru Kuwajima, photos by Ikuru Kuwajima

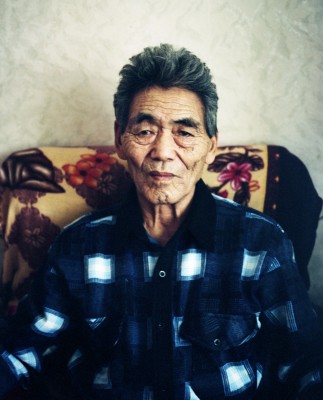

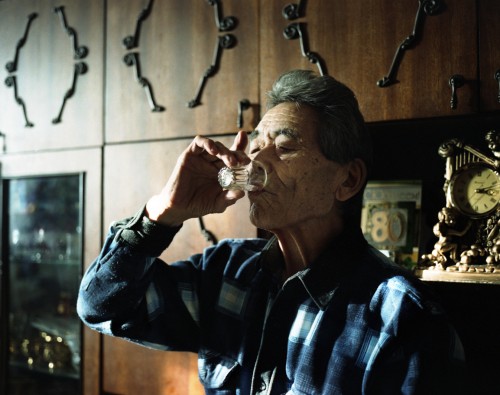

Tetsuro Ahiko has his eyes closed now. The vodka has begun to affect him, and he rocks a little towards the battered cassette player from where the music―a shrill chorus of young girls’ voices―is coming. He starts to sing along under his breath: “Shoulder to shoulder, I walk to school with my brother, thanks to the soldiers… thanks to the soldiers that died for the nation, for the dear nation.” As the last voices die away, the room, in a cramped Soviet flat in a crumbling block in a impoverised town in the middle of the icy, windswept steppes of Kazakhstan, comes back into focus. “I forgot Japanese,” he says. “But I didn’t forget the songs that I listened to in my childhood.”

This cassette of World War II military songs, long since forgotten as part of a shameful past back in Japan, is one of the handful of tokens he keeps of a life that was snatched away from him one day in 1948, when, instead of repatriating him from his military school on Sakhalin Island, Soviet troops put Mr Ahiko on a train to the Gulag work camps. More than 60 years later, Mr Ahiko is still here.

“Now I’m the same as all the people here,” he says. “I’ve got used to it.”

Tetsuro is the last Japanese man still remaining in Kazakhstan out of the hundreds of thousands Stalin shipped to the most desolate parts of the Soviet Union, putting them to work in mines, in construction, and in factories. More than a tenth of them died due to the brutal working conditions.

“I think all the Japanese have gone back apart from me,” he says. “There was one from Lake Balkhash, who went to Japan because his wife was ill, and there was also one in Almaty. I think there are no other Japanese here now.”

Tetsuro’s ordeal began with a clerical error. In 1948, Soviet soldiers were preparing to repatriate the Japanese citizens left stranded by their annexation of Sakhalin Island in the Russian Far East. Testuro’s name was on their list, but because of a transliteration mistake, the spelling didn’t match that in his papers.

“I was in prison on Sakhalin for half a year, while there was an investigation,” he says. “They beat us, and people wanted to get some information from me, but I couldn’t speak, I couldn’t speak Russian, so I didn’t answer. Afterwards, I was sentenced to 10 years of prison and I was sent here. It took about one year, the whole journey.”

On the train, a group of older prisoners called him over to them, pretending to befriend him. But when he left his seat, one jumped into his place and stole his mattress and all his clothes, leaving him to shiver through the rest of the journey, without even an overcoat. On arrival in Kazakstan, he spent a month near the city of Pavlodar waiting to be sent to the camps. There were more than 60 prisoners, he remembers, crammed into a tiny hut whose broken windows did little to keep out the icy cold.

“It was impossible even to move, or even to lie down to sleep. You could only sit. I was almost naked, even in January,” he says. “One person looked at me, and brought from somewhere a t-shirt. I still remember it. It was so dirty that it seemed like it was made of leather.”

Then the orders came. He was to work in the copper mines in Jezkazgan. He was just sixteen.

“We were young and healthy, but after working three months in the ore mine in Jezkazgan, we were not healthy any more,” Tetsuro remembers. “After that I was sent to Spassk. It was the camp where they sent people who were almost dead. The logo was ‘today you will die, and tomorrow I will’.”

Many of Tetsuro’s fellow prisoners were Japanese, but there was little camaraderie. “We didn’t speak to each other; we just thought, ‘I want to eat, I want to eat’. That’s what I was repeating in my head all the time. I was just thinking ‘I want to go home, I want to go home.’ ”

But unlike almost all the other Japanese in the camps, when Tetsuro was finally released in 1954, he did not go back to Japan. “The administrators of Karlag [the Kazakh camp system] maybe mistyped, or made a mistake, in the list of prisoners in Karaganda,” says Shunsuki Ajikata, a former employee of Japan Sakhalin Compatriot Exchange Association, which tracks down Japanese still stranded after Russia’s annexation of Sakhalin.

By 1956, when the Soviet Union made its last major repatriation to Japan, it had sent 510,000 prisoners home. But Tetsuro was not among them. Classed as a political prisoner, he had to report to the police in Aktas every three months. He was not given proper papers, which meant he was barred from official employment.

“There were free rooms at the military base, so I slept there on the floor. I didn’t have any clothes besides what I wore at the camp, and I slept in my clothes. I didn’t have money to buy food.” He survived on scraps from a miners’ canteen. “I couldn’t go there during the day because there were too many people, so at midnight I collected their leftovers. I’d bring all that back home, sit down and eat.”

Eventually, Tetsuro did find work, as a labourer in a cement factory. There he met Katya, an ethnic German born in the Russian city of Saratov, who he married, taking on her two young children. Shortly after in 1959, Tetsuro’s father, who had learned his whereabouts from returned prisoners, managed to get a letter to him, asking him to leave everything and come back to Japan. It’s unclear whether Tetsuro’s status as a political prisoner would have allowed him to go. He refused either way.

“Katya was worrying, crying, afraid I would leave for Japan,” he remembers. “But I didn’t want to go. I wrote back to my father that I was abandoned by my family in 1945, was hungry, cold and lonely, but survived, was arrested in 1948 and sent to Karlag. I couldn’t leave my children and wife and risk them repeating my destiny. My father was offended and didn’t write to me again.”

His younger brother Yujo later told him: “When father received your letter, he grew very old at once.”

After that, Tetsuro had no contact with home for a further 37 years. It was only in 1993, in the thaw following the collapse of Soviet Union, that the Japan Sakhalin Compatriot Association managed to track him down. The following year, 46 years after he first boarded the train to the Gulag, the association flew him to Japan to meet his brothers and sisters, who lived in the city of Sapporo on Japan’s most northerly island.

“I’d absolutely forgotten the language, I had to have an interpreter,” Tetsuro remembers. He pulls out an old album of photos from the visit, and shows a picture of him sipping tea from a bowl, sitting cross legged next to his brother, both of them dressed in ceremonial Japanese clothing, and another with his sisters sipping beer and eating sushi. His father had since died.

In 1996 he went a second time, this time with his daughter Irina, and it was then that the Japan Sakhalin Compatriot Exchange Association made an offer to bring Tetsuro back to Japan. The offer was generous. The family would get all travel expenses, six months’ training in Japanese language and culture at a special facility north of Tokyo, a flat in Hokkaido, and a monthly pension. But Tetsuro turned it down.

The standard of life in Aktas is low, even for Kazakhstan. The average monthly salary sits well below the $500 a month average for the country, and the town, with its crumbling blocks and dusty, pot-holed streets, has seen few benefits from Kazakhstan’s recent economic growth. The climate is harsh. Winter temperatures frequently dip below -30℃. The only features that break up the surrounding treeless steppe are a sprinkling of mines, and giant Soviet era industrial plants, belching smoke into the air.

But Tetsuro has made his home here. In 1993, he had just retired, and was looking forward to taking fishing trips to the lakes and rivers nearby, And anyway, he didn’t want to live off charity. “If I went to Japan, I would be living on a government allowance as if I was a beggar,” he says. “But here, I have earned my pension. I don’t want money from strangers.”

Last summer, the association again offered to resettle him, his Russian wife Elena, one of his children, and their family. Again he refused, this time because he didn’t want to leave any of his family behind. Tetsuro has several grandchildren now, from both his daughter, Irina, who is married to a Russian, and his son Teruo, who recently divorced his Ukrainian wife. And the Japan Sakhalin Compatriot Exchange Association is only prepared to resettle one child and one set of grandchildren.

But as Tetsuro approaches 80 years old, it’s clear he yearns to end his days among his own people. “If the children knew Japanese, probably we could go there,” he sighs, when I press him on the subject. His Russian second wife, Elena, looks at me with increasing suspicion, and when I ring back after my visit to clarify aspects of his story, his daughter Irina begs me to leave them alone.

“Please don’t call any more,” she asks. “Every time he speaks to you about this, he is upset for days afterwards.” So for now Tetsuro is left to rely the cheap Japanese souvenirs he has brought back from his trips home: a plastic doll in a kimono, some wall hangings of Japanese calligraphy, a few ornate plates and bowls, and his cassette of old war songs.

That, and the one aspect of Japanese culture he has always carried with him. “I still bow,” he says with a dry laugh. “From the first time I came here, I would always do it, even to the people who were working in the camps. I would go and take a bow.”

[…] This post was mentioned on Twitter by Charles Mabbett, Jonathan Dresner. Jonathan Dresner said: The last Japanese man remaining in Kazakhstan: A Kafkian tale of the plight of a Japanese POW in the Soviet Union http://bit.ly/h7ltgx […]

[…] Japan Subculture Research Center's blog, Richard Orange and Ikuru Kuwajima tell the story [en] of “one Japanese POW trapped in the Soviet Union after the end of the Second World […]

[…] Japan Subculture Research Center‘s blog, Richard Orange and Ikuru Kuwajima tell the story [en] of “one Japanese POW trapped in the Soviet Union after the end of the Second World […]

Wow, what a story and what an interesting read. Thanks for sharing this.

An amazing life, lived one day at a time. And, I can’t believe how good-looking this man is, nearing eighty. He must have been quite a catch in his prime…

Yeah, it’s an amazing story and he seems very philosophic and stoic about it all. I wish there was something we could do for him but doesn’t want charity. He seems like quite a character.

[…] [link to article] […]

Thank you for sharing the amazing life story.

There must be so much more to tell behind those photos, behind those eyes. People of old school to whom dignity is everything.

All the best.

[…] The last Japanese man remaining in Kazakhstan A Kafkian tale of the plight of a Japanese POW in the Soviet Union […]

[…] Closing: Kafka-san; tip of the iceberg?; junk fees and foreclosure; too lazy; secret air travel; pot of gold; is it […]

[…] The last Japanese man in Kazakhstan. […]

[…] The last Japanese POW in the USSR: http://www.japansubculture.com/2011/02/the-last-japanese-man-remaining-in-kazakhstan-a-kafkian-tale-… […]

[…] This post was mentioned on Twitter by Virgil Dobjanschi and Rie Rubin, John Granger. John Granger said: Heartwrenching tale of the plight of a Japanese POW in the Soviet Union. http://bit.ly/edDvzz […]

Even though he did not speak much there were some life philosophies that came into picture.

The man’s actions say much about him. I have great respect for him. I wanted to offer him a small compensation for cooperating with the article but Ikuru was certain that it would insult his sensibilities. Maybe, he would except some green tea. He seems like a quite a wise old man.

I respect him for what he did.

Wow. A truly amazing story.

Its interesting, I would like to express gratitude to this increadible man for being such high principel person. But, Japanese has to live in Japan, besides that he should not consider him self as a begar in japan , because he has paid his duty during the war and after it was over by suffering on our harsh kazakh land. NIPPON BANZAI

What a courageous man to make a life out of such difficulty.

[…] few Japanese POWs stayed on in Kazakhstan even after the others were repatriated. Click here for the story of the “last remaining Japanese POW” who was left behind due to bureaucratic […]

[…] warmth and generosity. I am personally a bit worried for this interview, because we read an article that morning about Tetsuro on a Japanese site, where Tetsuros wife begged the writer of the […]

Great article. Maybe because I am an expat in Japan, sort of in the reverse direction, it made me cry. I see that he was still alive last year and coming to Japan with a message of peace.

https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2017/12/29/national/japanese-man-held-soviets-kazakhstan-wwii-brings-message-peace-tokyo/#.WvPMj3–lpg

He had at last put on a little bit of weight. He is my hero.

Incidentally, Michel Louyot, a French novelist wrote a book, “Lorraine” I think, about German soldiers from Lorraine that had become “deracinated” and relocated in Russia.

Tetsuro-san passed away this last week. An admirable man.