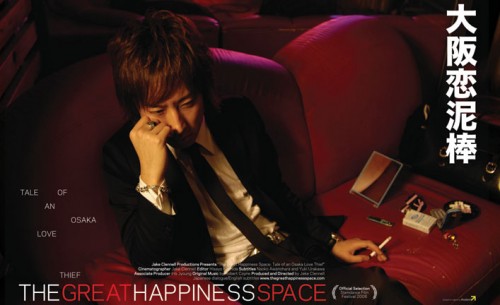

Not a new film but a unique one to be sure, The Great Happiness Space: Tale of an Osaka Love Thief is a 2006 documentary by UK director Jake Clennell that delves into the very visible yet mysterious world of the host club. The Wikipedia entry on host clubs gives a fairly good summary of the business we see in the movie–women paying exorbitant amounts of money to have guys fawn over them–but a trip into The Great Happiness Space puts the industry’s underbelly on display for all to see.

Using popular Shinsaibashi host club Cafe Rakkyo as its setting, the documentary takes viewers on a slow, twisted tour through the world of owner Issei–a mega-popular “charisma host”–and his fellow employees as they guzzle pitchers of beer and hustle women into buying over-priced bottles of champagne in order to win their affections. We soon learn those affections are less the typical lighting cigarettes and wiping glasses type, and more a combination of playing the older brother/boyfriend role and, embarrassingly, wrestling with drunken girls in the hallway.

The documentary switches reality TV-style between private interviews with hosts and clients and scenes of messy partying or private conversations. We learn that host clubs are different from their hostess counterparts in that hosts often use their customers’ insecurities against them, very apparently rotating between groups of girls and persuading them to throw down more cash than their neighbors. The interviews reveal hosts that are apathetic or distrusting of women and clientele who at times appear obsessed, virtually selling their bodies for enough cash to drop into the Rakkyo boys’ wallets. The entire thing gets bizarre after a while, and between glimpses of the sunny outside world from down dark corridors where the subjects reveal intimate details of their cyclic lives, we wonder if any of them really want to be there at all.

The entire ordeal is recorded a bit too perfectly, however, and viewers may begin to suspect the all-too-candid scenes of romancing and other frolics might be staged. Issei turns the tables on us, however, by suggesting to the camera man that one of his over-zealous suitors might be using the interviews for her own agenda, trying to seduce him by playing up her devotion to the camera.

Towards the end of the movie, while Issei complains his life of booze and persistent women has become “shindoi” (tiresome or bothersome), as a viewer towards the end I couldn’t help but think the film had become so as well–watching these peacock men act like they’re in middle school with these drunken girls night after night in near slow motion. The film was fascinating but at the same time tiring to watch, and one can’t help but wonder what happened to the poor kids featured after the cameras were gone.

Predictably, The Great Happiness Space revealed almost no happiness at all, providing us instead with a glimpse into a group of hollow young men “struggling” to pad their wallets with cash and destroying themselves in the process. For those who are interested in Japanese subcultures and haven’t seen this award-winner of a documentary, give it a rent, a borrow, or a (legal) download. But once is probably enough.

Jake’s Notes:

There are certain moments in the film where things seem slightly staged—but the director is able to capture Issei-san, the number one host, very tired, drunk and at his most vulnerable and in those moments, the whole facade is stripped away. It contrasts well with the formal interviews in which Issei prattles on about the job of a host being “a salesman of dreams.” Towards the end of the film, he admits that that the essence of a host’s job is lying to the women who come there and telling them that they love (like) them when actually that is not the case. The translation is “we lie that we love them.” The actual words:「好きじゃないけど好きだというような嘘を言うのがホストなんですよ」are closer to saying, “A host’s job is to tell a woman that we like them when we really don’t and it’s a kind of lie.” And in his viewpoint, half of the customers understand that it’s a lie.

The chapters on host clubs and hostesses in TOKYO VICE cover much of this ground so I won’t repeat it here but I think the film certainly illustrates what I was trying to say in a very concrete manner.

What Issei-san says about the life of a host, can also be equally applied to the life of a hostess, cabaret girl, or stripper. Of course, it’s not only in the world of hosts and hostesses that people lie about their true feelings, or profess fondness they don’t have, to get something they want or need. For the denizens of Japan’s 水商売 (mizu-shobai/night-life) —they lie for money. In bars like Heartland or Velours or any where else expats gather, men can found lying to get laid. The motivations are different, the methods are often the same.

The movie is also about the massive webs of deception and expectations in human relationship. While many of these women in the film seem to be devoted to Issei-san, making him look like a completely despicable sociopath–they are also admittedly cultivating relationships with other hosts at other clubs as well–and this appears to wound the protagonist. He is visibly upset that they are seeing others hosts besides himself and frequenting other clubs than his own. Even in the world of hosts, loyalty and a kind of monogamy are values prized but rarely won.

In his private moments, it appears that Issei and the other hosts are not particularly happy and unable to cultivate healthy relationships with members of the opposite sex. This often happens to hostesses as well. I won’t credit the yakuza with much wisdom but the words of one gang boss come to mind when watching this film. “ヤクザは裏切られちゃってもいいです。人を裏切っちゃだめです。人を裏切ったら自分のことも使用できなくなる。自分のことを信用できないと、そして他人も信用しなくなるんだ。それは寂しい生き方だ。男の生き方じゃない」 As a yakuza, it’s okay to be betrayed. Don’t be the one to betray other people. If you betray (double-cross) others, you won’t be able to trust yourself. And if you can’t trust yourself (to be loyal, to keep your promises) you’ll grow not to trust others as well. And that’s a lonely life. And not the way a man should live.”

It’s very hard to trust anyone if you are constantly deceiving other people and not honest yourself. It doesn’t come as a great surprise that most of the hosts seem to have no personal lives.

Even in the current depression, the host clubs in Kabukicho are still thriving. Almost all of them have some yakuza backing while professing to be running clean operations. The yakuza make huge kickbacks from debts collected from deadbeat customers and protection money paid to them from club owners but in general, the only people yakuza find more despicable than themselves are “hosts.” It’s an interesting distinction.

The night life in Japan revolves around in pretending to have feelings that are not there, about pretending to care when you do not, and doing so for your own profit often at the expense of the other person. I would say that probably applies to much of interpersonal life in Japan. Host and hostess clubs in Japan do help stave off loneliness and while it’s a little less honest than say psychotherapy, in the end, there’s not that much different. When the money runs out, the “therapy” ends. There’s a Japanese saying that summarizes the film very aptly:

金の切れ目が縁の切れ目(Kane no kireme ga en no kireme)/The end of the money flow is the end of the relationship.

I have seen this as well and its a very interesting look at this Japanese subculture.

Loved this film! I am a former Roppongi hostess turned stripper and always lament not having visited the male mizu shobai establishments.

Karen-sama

You and I definitely probably have some common friends. Thanks for writing to the blog and to me. We’ll hit a host club next time you hit town.

I lived in Tokyo for thirteen years. We’ve been back in the USA for a little over two years and still enjoy a window into various Japanese subcultures. This is one I obviously didn’t know much about so, when I found it on Netflix/Roku, I settled back with a Sapporo and a sushi selection from my local Asian grocery.

Very interesting. I love being transported back to the fascinating world we left behind.

[…] A documentary on host clubs (entitled “The Great Happiness Space”) came out in 2006 and writer Jake Adelstein said it best in his review: […]

It’s been over a year since this article was published, but I still find it as the most valuable and intriguing look on the film. How the artifice of the hosts work to lure the hearts of their customers, while the girls seem totally aware of that artificiality is what draws me to this bold yet delicately teetering virtual love game. Uniquely this exchange seems functional only in the context of the Japanese culture.

Anyway, just came across this website and love it in general. Will come back for more.

Thanks for the great post Sarah and Jake!

We will be posting an interview with the director this week. Thanks for writing in!

Amazing comments and observations.

Just the right level of detail, with a perception of the content that kept me intrigued and thinking.

Two thumbs up. Bookmarked this website.

Thank you! Please see our interview with the director Jake, elsewhere in the blog.

i love the film. Puts a new look on japanese culture and something i only have seen in fictional books.