reposted from the total crime substack

by guest contributor Chris Summers

The yakuza, Japan’s infamous organised crime syndicates, have gone into a death spiral in recent years and Jake Adelstein says it is partly due to an incident at a sumo tournament in 2009.

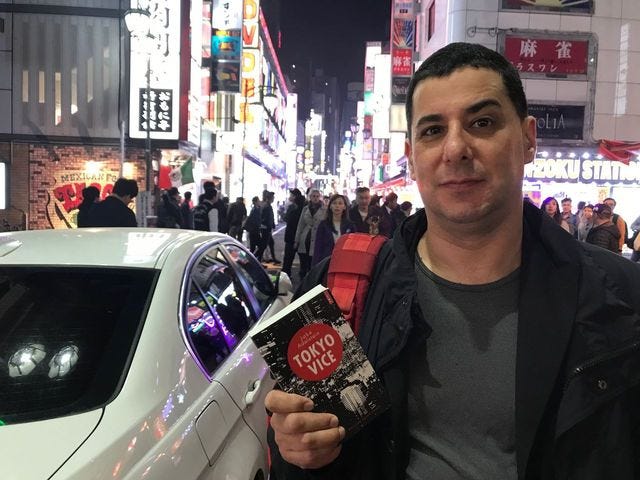

Adelstein’s knowledge of all things yakuza comes despite him suffering one major disadvantage – he is not Japanese, and was born thousands of miles away in Missouri.

But after the “skinny Jewish kid” moved to Japan in the late 1980s to study Japanese literature he found himself, in 1993, being offered a job as a journalist on Japan’s biggest newspaper, the Yomiuri Shimbun.

He says: “I was assigned to the crime beat and eventually started covering the yakuza as part of my beat. My unique position as an American journalist in a Japanese newsroom gave me a particular perspective and access, which I used to dig deep into the criminal underworld.”

Adelstein would go on to become one of the most respected experts on organised crime in Japan.

He tells me the yakuza evolved from groups known as bakuto (gamblers) and tekiya (street vendors), which dated back to the Edo period (1603–1868).

He says they were involved in gambling and other black-market activities and gradually organised into more formal associations, leading to the modern yakuza organisations, which grew in the years after Japan’s defeat in World War Two.

There are several major yakuza syndicates – Sumiyoshi-kai, Inagawa-kai (of which the Yokosuka-ikka, pictured, were part) and Matsuba-kai – but the big daddy of them all is the Yamaguchi-gumi, which Adelestein describes as the “Walmart” of yakuza.

The Yamaguchi-gumi, which has its roots in the Kansai region (Osaka/Kobe), is made up of several smaller gangs, one of which is the Goto-gumi, which became Adelstein’s bête noire.

The eponymous godfather was Tadamasa Goto, a character who villainy is imbued with a darkness redolent of some of the sicker manga comics.

At the heart of Tokyo Vice is the story of how Goto obtained a liver transplant in the US after a murky deal with the FBI.

Standing this story up – as they say in journalism – almost got Adelstein killed.

His life has recently been dramatised in a highly successful TV drama, Tokyo Vice, starring Ansel Elgort and Ken Watanabe.

In one of the first episodes Elgort, playing a young Adelstein, delving into a mysterious insurance firm which turns out to be a yakuza front company.

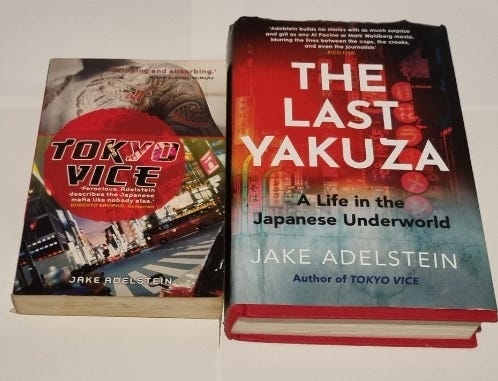

The TV series is very loosely based on his first book, which came out in 2009.

And it was in July that year Adelstein says the yakuza slipped up big time.

Adelstein, who is now 55, sat down for an interview with me over Zoom last week and this is what he told me.

“One of the things that you could say caused the downfall of the yakuza was in 2009 while Kenichi Shinoda, the leader of the Yamaguchi-gumi, was in prison, a bunch of Yamaguchi-gumi members went to the Nagoya sumo tournament and they got front row seats.”

They were members of the Kodo-kai, Shinoda’s ruling faction, who were based in the city of Nagoya.

“They sat there in front of the cameras, sending a message to their boss – because prisoners are allowed to watch sumo – ‘hey man, we’re here, we’re for you, we’re around’.”

But he said the “silent signal” to Shinoda had unforeseen consequences.

“There had been an agreement between the police and the yakuza that the yakuza would stop parading themselves on TV so the National Police Agency (NPA) felt like the agreement had been violated and they were very angry.”

Adelstein (pictured below with former Yamaguchi-gumi boss Satoru Takegaki) says the NPA went to NHK – the Japanese equivalent of the BBC – and insisted they report their anger and it became a scandal.

“It was one of the boiling points, one of the many things that made the National Police Agency say ‘fuck you guys, you’ve become uppity, too powerful, you’re not keeping your agreement, so we’re going to take you out’.”

The head of the NPA, Takaharu Ando, persuaded prefectures – the Japanese equivalent of states in the US – to bring in anti-yakuza legislation which would eventually cripple the gangs.

Adelstein said the police did not trust the National Diet – or parliament – because there were too many MPs who were in the pocket of the yakuza.

The brains behind the legislation was anti-yakuza lawyer Toshiro Igari, who died mysteriously in 2010.

“Igari, who designed these ordnances, told me ‘we would never have got these lawyers passed on a national level so we’re gonna sneak around the parliament and get them done on a local level, which is exactly what they did.”

He said he had heard the NPA even went to the prefecture governors and threatened them with the consequences if they did not pass the anti-yakuza legislation.

“Anecdotally it sounds like they went to the governors and said ‘if you oppose this or don’t push it forward, we have a nice file on you which we’d be happy to share with the journalists’ and the governors were suddenly, oh great, let’s pass this legislation.”

“There is no national law which criminalises the yakuza. It is all local laws which were done over a two year period [2009-2011].”

The first place to pass these laws was Fukuoka, in the far west of Japan – which was home to the Kudo-kai (a separate yakuza organisation, not to be confused with the Kodo-kai) – and the last were the country’s two biggest cities, Tokyo and Osaka.

The laws prevent corporations and small businesses from doing business with yakuza – who are often distinguishable by their tattoos and sometimes by missing fingers (pictured) – and even criminalises them if they pay extortion money.

Suddenly those businesses who had found it easier to pay up or stay quiet, decided dealing with the yakuza was not worth the hassle.

The law also forced banks, phone companies, car rental firms, gyms and building owners to draw up contracts which included a clause asking customers if they were yakuza members.

If a yakuza denied their membership, they were committing fraud and could be prosecuted.

Overnight yakuza found themselves unable to open bank accounts, rent or buy offices, homes or cars, join gyms or golf clubs or even buy a mobile phone.

What many outsiders, including me, found so strange about Japanese organised crime was how open it was.

Syndicates like the Kodo-kai would have offices in each neighbourhood and would proudly display their daimon (pictured), a corporate logo or crest which was of great importance.

I asked Adelstein if this visibility was a flaw, in hindsight.

But he said: “I don’t think that was a big mistake. It was good for business and for recruiting talent. The PR was a plus, not a minus. The problem wasn’t that they should have kept a low profile.”

“The problem was that they began to openly challenge the police and increasingly were involved in large scale financial activity that threatened the economic foundations of Japan.”

“The yakuza overstepped their boundaries and the response of law enforcement, particularly the National Police Agency, was to draft a long-term plan to effectively neuter and dismantle the yakuza groups, which has been tremendously successful.”

The anti-yakuza legislation threw a massive spanner in the works for Japanese organised crime, which has been in full retreat since 2011/12.

Adelstein says: “Their numbers have dwindled. There were 80.000 yakuza in 2011. Now there’s 24,000.”

Former yakuza who gave up the rackets and decided to go straight also found it extremely hard, as Adelstein explains in his latest book, The Last Yakuza.

Saigo – the central character in the book, who is a composite of several yakuza who Adelstein knew over the years – ends up working for a shady estate agent selling or renting “jikobukken”, a uniquely Japanese word meaning “tainted properties”.

In Japan estate agents must declare if someone has been murdered or committed suicide in a property in the last two years.

Another elderly gangster, who is unnamed, summed up the reason for their decline to Adelstein in The Last Yakuza: “We got too big. Japan isn’t Mexico. We’re not going to take over the country. A few more upgrades to the law and we’re gone. Maybe we’ll exist as a cultured treasure.”

Adelstein says another event which led to the perception of the yakuza as having got too big for their boots, was Tadamasa Goto’s refusal to leave the Westin Hotel in Tokyo in 2000.

“There would never have been organised crime exclusionary ordnances if it weren’t for Tadamasa Goto. Because the whole genesis of this began with him being in the Westin Hotel and refusing to leave the hotel, even after customers complained.”

“The manager of the hotel asked him to leave, he made the manager bring him the agreement he signed when he checked in and said ‘you don’t have anything here forbidding yakuza using the facilities, so I’m just a customer and there’s nothing you can do’.”

Adelstein says when Goto finally left, he left a deposit which the hotel wanted to return to him without getting in trouble.

So the Westin Hotel spoke to Igari and he advised them to draw up a new agreement with customers which included, in the fine print, a stipulation that the guest was not a yakuza. Signing the agreement was tantamount to fraud for a yakuza.

“So that’s how it all began. If you want to blame the decline of yakuza on anyone, blame it on Tadamasa Goto.”

Another yakuza own goal was when the Yamaguchi-gumi hired a private detective agency to buy the mobile phone numbers of police officers and then used it to “obliquely threaten” them and their families.

But while it might be good news for Japan, the decline of the yakuza is obviously bad news for journalists who specialises in covering them.

Fortunately for Adelstein, he is not only a successful author but has also diversified into writing about other facets of Japan.

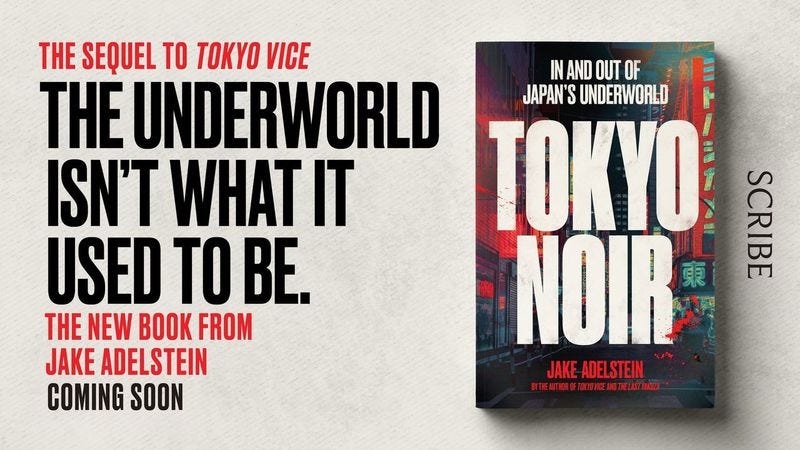

This summer his third book, Tokyo Noir, will be coming out.

“It picks up where Tokyo Vice left off, and it explains why I no longer felt I needed to have police protection.”

“It has a long section about this period of time when I was doing corporate due diligence, basically looking at companies which were run by yakuza and telling my investment banker bosses who they could invest with and who they couldn’t, which was a fun job because it was like being a private eye.”

Tokyo Noir also contains considerable detail about Igari’s death in Manila.

Adelstein told me: “I think he was whacked. I got a copy of the autopsy from the local authorities, which ruled out suicide. Before he died in the Philippines, he told his editor that he was considering the possibility that he might be killed.”

“He made lot of enemies. The problem is, I’m not sure which landmine he stepped on, but I know that I was his last client.”

“I asked him to handle a lawsuit against Tadamasa Goto. He took the case, took a vacation and never came back to Japan alive.”

As the yakuza slowly faded out, Adelstein began to take an interest into other scandals, such as that surrounding the Tokyo Electric Power Company (Tepco), which ran the Fukushima nuclear power station.

“There came a time when many things, especially the nuclear meltdown (at Fukushima, following the 2011 tsunami), made me realise there are things much worse than the yakuza. It was a wake-up that there are bigger problems in Japan than these guys.”

Adelstein has also become an award-winning podcaster – his voice co-stars with Shoko Plambeck in The Evaporated, a fascinating look at the peculiarly Japanese art of making yourself disappear.

He says of the yakuza, “Historically they are interesting, but I write about them less and less.”

Chris Summers started out on weekly newspapers in Hampshire in 1990, then graduated to the Gloucester Citizen where he covered the exploits of serial killers Fred and Rose West. That got him hooked on crime and he has specialised in it ever since. He worked for the BBC for 18 years and in 2003 interviewed the co-founder of The Crips, Stanley “Tookie” Williams on Death Row in San Quentin, two years before he was executed on the orders of California’s Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger. He currently works for The Epoch Times in London, covering crime and courts. He launched a Substack in March 2024 which is a mixture of new articles and updated material from his archives.