(special contribution from Steve McClure)

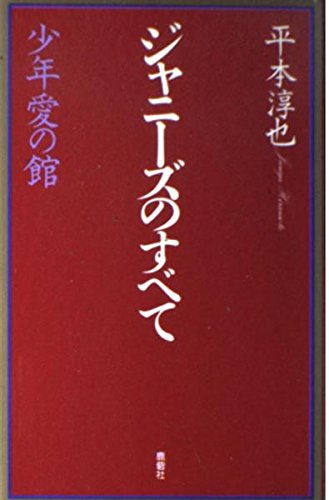

Editor’s note: Japan’s most beloved pederast (a male who sexually assaults young men) , Johnny Kitagawa, died last week. He was an idol maker, the brains behind such super male idol bands as SMAP, Kinki Kids, and an entertainment legend. He was also so powerful that the seedy and dark side of his life was swept under the table even after his death.

There were some in the media that dared challenge the sleazy smooth Svengali. Weekly magazine, Shukan Bunshun ran a series of well-researched articles in 1999 describing how Kitagawa systematically abused young boys. Kitagawa then sued the publisher for libel but despite the testimony of alleged rape victims interviewed for the piece, the Tokyo District Court ruled in his favor. They ordered the publisher to pay 8.8 million yen in damages to Kitagawa and his company in 2002.

However, The Tokyo High Court overturned this decision in July 2003. They concluded that the allegations were true. “The agency failed to discredit the allegations in the detailed testimony of his young victims,” ruled the presiding Judge Hidekazu Yazaki. The case stood. The story was barely a blip in the Japanese media horizon. In an entertainment world where Johny’s stable of young boys was a prerequisite to ratings success, his ‘indulgences’ weren’t deemed worthy of reporting.

Johny granted few interviews–here is the story of one of them:

My interview with Johnny

By Steve McClure

It was only after I’d interviewed Johnny Kitagawa that I realized I’d scored a bit of a scoop.

“You interviewed Johnny? That’s amazing – he never does interviews,” my Japanese media and music-biz colleagues said. “How on earth did you manage to do that?”

It was 1996 and I was Billboard magazine’s Japan bureau chief. I was hanging out with an American producer/songwriter who had written several hit tunes for acts managed by Kitagawa’s agency, Johnny’s Jimusho.

“Want to hear a funny story about Johnny?” Bob (not his real name) asked me.

“Sure,” I said.

“Well, the other day, Johnny told me he’d discovered a promising male vocal duo. I asked him what they were called.

“‘I’m going to call them the Kinki Kids,’ Johnny told me.

“I told him that ‘kinky’ means sexually abnormal in English slang.

“‘Oh, that’s great!,’ Johnny said.

Bob and I laughed.

“Say, Steve, would you like me to set up an interview with Johnny for you?” Bob asked.

I told him that would be swell.

Some days later I was informed that Kitagawa would grant me an audience at his private residence. I was enjoined not to reveal where the great man lived (it was Ark Hills in Akasaka, for the record).

I showed up at the appointed day and hour, and rang the doorbell of the condo high up in one of the Ark Hills towers. A browbeaten middle-aged woman answered the door. Evidently a domestic of some kind, she said I was expected and asked me to come in. She led me into a garishly decorated living room full of Greek statuary, Louis XV-style furniture and sundry examples of rococo frippery. There were no Ganymedean cup-bearers offering libations or any other signs of sybaritic excess.

I was ushered into the presence of the pop panjandrum. Johnny was sitting in an armchair beside a window with a stunning view of Tokyo. He was small, bespectacled and unprepossessing. If you saw him in the street, you’d never imagine he was the notorious and feared Svengali who had a stranglehold on the geinokai (芸能界/Japan’s entertainment world).

After we exchanged pleasantries, I got down to business. I asked Johnny about his early life in Los Angeles. “My dad ran the local church,” he told me without elaboration in a quiet, rather high-pitched voice. I later found out that Kitagawa père had been the head of a Japanese American Buddhist congregation in L.A.

Johnny was equally vague about when he first came to Japan. He reportedly arrived while serving as an interpreter for the U.S. military during the Korean War.

This set the tone for the rest of the interview – it was hard to get a straight answer out of Johnny, at least when it came to his personal history. He was more interested in talking about all the boy bands he’d groomed and propelled to stardom during his long and extraordinarily successful career.

Johnny told me how he got his start in showbiz when he saw some boys playing baseball in a Tokyo park, and later molded them into a pop group called The Johnnies. That set the template for the rest of his career – scouting for boys and using them as raw material as his pop production line churned out an endless succession of unthreatening quasi-androgynous male idol groups.

A classic showman, Johnny said he was more interested in live performances than records. He made his mark with coups de theatre like having ’80s male idol act Hikaru Genji do choreographed routines on roller skates.

“Once you release a record, you have to sell that record,” Johnny said. “You have to push one song only. You can’t think of anything else. It’s not good for the artist.” The Johnny’s stable of acts has nonetheless racked up dozens of No.1 hits over the years.

Johnny’s English, like that of many longterm expats, was quaintly fossilized. I could hear echoes of ’40s and ’50s America when he said things like “gee,” or “gosh” when answering my questions.

Soon after the interview began, the browbeaten obasan put a steaming dish of katsu-curry in front of me. I begged off, explaining that I’d just eaten lunch. This didn’t prevent the arrival of another dish soon after: spaghetti and “hamburg” steak, as I recall. Hearty fare for starving young idol wannabes was my take on the menu chez Johnny.

Having decided that “Are you or have you ever been a pederast?” might be somewhat too direct a question to put to the dear old chap, I lobbed a series of softball queries with the aim of establishing a friendly rapport. But even the most gently tossed questions elicited amiable but frustratingly vague answers from Johnny.

In the silences between his frequent hems and haws, the wind whined like a sotto voce banshee through the slightly opened window.

Johnny did tell me that he received 300 letters a day from guys wanting to sign up with his agency. I wasn’t sure if he was boasting or bored.

The time came to leave, and Johnny accompanied me to the door. “Come back anytime,” he said with a friendly smile as he waved me goodbye.

As I made my way down the hall to the elevators, I saw the finely chiseled profile of a young man peeking from around a corner, looking in my direction. He caught a glimpse of me and retreated. I resisted the temptation to tell him the katsu-curry was getting cold.

Sadly, I didn’t take up Johnny on his kind offer to come up and see him sometime.

[…] case, Johnny & Associates still ruled the airwaves. Their popular groups like SMAP, Arashi, and KinKi Kids dominated Japanese TV. There were members on variety shows, samurai dramas, cooking programs—it […]

[…] case, Johnny & Associates still ruled the airwaves. Their popular groups like SMAP, Arashi, and KinKi Kids dominated Japanese TV. There were members on variety shows, samurai dramas, cooking programs—it […]

[…] case, Johnny & Associates still ruled the airwaves. Their popular groups like SMAP, Arashi, and KinKi Kids dominated Japanese TV. There were members on variety shows, samurai dramas, cooking programs—it […]

[…] case, Johnny & Associates still ruled the airwaves. Their popular groups like SMAP, Arashi, and KinKi Kids dominated Japanese TV. There were members on variety shows, samurai dramas, cooking programs—it […]

[…] case, Johnny & Associates still ruled the airwaves. Their popular groups like SMAP, Arashi, and KinKi Kids dominated Japanese TV. There were members on variety shows, samurai dramas, cooking programs—it […]

[…] case, Johnny & Associates still ruled the airwaves. Their popular groups like SMAP, Arashi, and KinKi Kids dominated Japanese TV. There were members on variety shows, samurai dramas, cooking programs—it […]

[…] case, Johnny & Associates still ruled the airwaves. Their popular groups like SMAP, Arashi, and KinKi Kids dominated Japanese TV. There were members on variety shows, samurai dramas, cooking programs—it […]