By Sandra Barron for JSRC

originally posted on March 9th, 2011

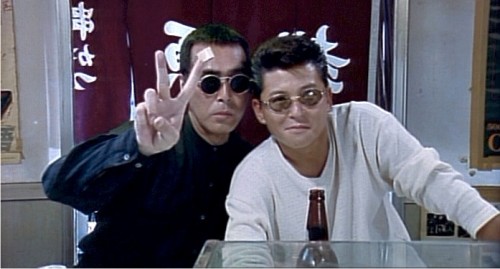

It was one of those nightmare commutes. A crowded train finally pulled up to a rush-hour platform, dense with people who’d already been delayed, who were already running late, and were spending this purgatorial time pushed up against piles of equally inconvenienced fellow commuters. The doors opened and more people crushed in, but the train didn’t move. After a few agonizing minutes, his stoicism no match for the commuters around him, a JSRC writer gave up on riding this train and decided to document it instead. From the platform, he lifted his camera, bracing for glares from the trapped commuters. Indeed, snapping pictures of people in this state would be a good way to get a face full of one-fingered salutes from the poor saps stuck on the train. He got fingers in his shot – but not the ones he expected: Even under such duress, a bunch of strangers saw a camera pointed at them, and they flashed the peace sign.

This was an extreme situation, but not totally surprising. The spontaneous V-sign is as natural to many Japanese people as it is puzzling to visitors. Children seem to start do it as soon as they can control their hands – as evidenced by photos of crying toddlers who find the wherewithal through their tears to raise two little fingers. Kids are the most reliable peace-signers. While many (though certainly not all) adults outgrow the practice, get a bunch of school kids together and you’re guaranteed at least as many peace signs as there are uniforms.

A version of the Asahi Shimbun printed for kids, the Asahi Shogakusei Shimbun, went straight to the source and asked elementary school students why they did it. Three of the girls said they did it without thinking. “It’s like my hand just moves into that position by itself,” one fourth grader said. A sixth-grade girl interviewed said, “If I don’t do something with my hands, it’s like I’m just standing there.”

The legions of kids I used to teach, at least the girls, said they made the sign “kawaiku miseru tame”–to look cute. What about the other gestures the V-sign has morphed into and been accompanied by in snapshots – the double peace sign and the L near the mouth and the twisty sort-of-sideways thumbs up? “To look cute.” Okay, then. One of the kids’ mothers surveyed said “I do it less as I get older.” But people certainly don’t stop completely. Photos from Japanese girls’ nights out give US gangs a run for their money in number of hand signals raised, and, some men agree that it makes them look cuter. Entrepreneur and Japanese pop-culture purveyor Danny Choo wrote on his site, “I especially like it when the cute girls do a horizontal version of the V-sign next to their eye – kawaii [cute]!”

Winston Churchill wasn’t trying to look cute when he made the V for military victory during World War II. In occupied Europe, the V was a symbol of defiance against the occupying forces, and it was chalked on walls flashed as the now-famous hand signal as a show of resistance. It was even played by BBC radio in the form of the letter’s Morse code version, dot-dot-dot-dash, followed and echoed by the opening notes of Beethoven’s Fifth. Two decades later in America, the V-sign became the counter-culture’s well-known anti-war gesture.

How the gesture got so big in Japan remains a bit unclear. It has been variously attributed to post-war GIs in Japan, peaceniks Yoko Ono and John Lennon, an American figure skater, a camera commercial, and 1969 Woodstock festival footage. Jun Inoue, the lead singer in the Beatles-esque group The Spiders is said to have added the V-sign spontaneously during the filming of a Konica TV commercial in 1972. He may have been influenced by seeing American or British youth making the gesture on his previous trips abroad.

Another theory is that it was American figure skater and anti-war activist Janet Lynn who won over the hearts, minds and fingers of the photographed masses. In the 1972 Sapporo Olympics, she became beloved in Japan both for her artistic performance and for staying upbeat even after she fell on the ice. The theory goes that her frequent showing of the peace sign in subsequent print and TV media coverage in Japan won imitators.

It may not be possible to know which of these was the defining moment that set the template for the innumerable photos that would follow. The most likely answer is that there was no single moment when the official V-sign memo went around Japan. Whichever person or combination of images sparked it, the gesture, now far removed from its original meanings, entered the collective unconscious and there it has stayed. It gives people a way to stand out in photos or to increase group identity by all doing the same thing, suggests anthropologist Masaichi Nomura, quoted in the AsaSho.

It could happen like this. Consider an infant, waving its fingers and accidentally finding the V shape. The parents get excited, grab a camera. One says to the other, “He’s making the peace sign!” and they coo and clap and snap away. “Camera plus hand like this equals attention,” goes some series of synaptic connections in the infant brain. And thus, perhaps, a new generation of V-signers is born.

china too, it is everywhere .. and of course, girls combine it with cute poses when being fotographed.

I prefer the conspiracy/Illuminati theory re: Gaga’s all-seeing eye. I want this to be the next “kawaii” trend.

http://hdreactor.org/forum/topic/46/

The orientation of the hand whilst making the V-sign makes a big difference here in the UK so it’s amusing to occasionally see a photo of a smiling Japanese person flicking the V at you.

It is no longer a “peace sign” since most do not know that is its most recent origin. For those of us that lived through the 60’s and 70’s this was a sign that we shared daily with many – not in photos. I think this spread around the world. As the “photo culture” came into play, it stuck. I wish more people knew what it meant but most don’t.

It’s just as common as “cheese” is in the US. I like the Thai version too: thumb and index finger around the face, indicating the subject is handsome.

It’s rather common in Japan when taking a picture of someone to say, “ichi to ichi wa?” (what’s one plus one?), to which the subject responds “neeeeeee!” (two!) with a big smile. It’s the Japanese equivalent of “say cheese.” Naturally, people also put up two fingers to indicate “two” at the same time. Since the two fingers are the same as the peace sign gesture, and saying the word “peace” also bares your teeth, one custom probably morphed into the other. But I don’t know which came first.

Im pretty sure among the Japanese, the persistence of the peace while being photograph is a way of relieving their collective anxiety about being photographed. The Japanese are a high self-monitoring group, collectively plagued with appearance anxiety. Hence, flashing the peace sign when being photographed alleviates some of the anxiety. I suffered photo anxiety as a child and made strange faces while being photographer. However, as an adult such discomfort and self-monitoring has since disappeared. The collective peace sign in Japan is just another symptom of the low emotional quotient of Japanese society. Ten years in Japan and I still find that collective peace sign utterly annoying and if my half western child participates in this act, I will most certainly rid them of their fingers.

[…] Orgins of the peace sign in Japan […]

Stefhen fd Bryan:

I find your sophisticated analysis of Japanese society quite fascinating.

Except it’s not true. Plenty of other countries have people hold the V-sign when they take pictures. When I traveled to Peru, the teenage girls would also hold the V-sign when they took pictures. And this wasn’t metropolitan Lima, it was in the isolated, impoverished villages of the Andes – places populated by the indigenous peoples who are direct descendants of the Incan Empire. Same thing occurred in China; interestingly, the young people I took pictures with didn’t hold the V-sign, but the working class middle-aged people did.

I guess that speaks to the low emotional quotient and collective anxiety of indigenous Peruvian and working-class Chinese society.

Par exemple, il est possible de l’oreille Battle of Races Gems travers remplissant

réalisations et via compensation plusieurs obstacles.