Japan’s fishing traditions have long-been one of its most important aspects, surviving hundreds of years mostly on fish as well as obscure seafood such as sea urchins, squids and eels instead of red meat. But now with the world’s human population reaching new heights, many organizations have requested Japan stop hunting certain endangered species, particularly whales. Not all Japanese are ready to give up on whaling, particularly those from Japan’s Institute for Cetacean Research (ICR), which is funded by the government and continues to support whale hunting at a smaller capacity allegedly for the sake of “research” and maintaining the tradition.

Masayuki Komatsu, one of the Institute’s members and Japan’s deputy commissioner to the International Whaling Commission (IWC), published a book back in 2001 explaining why he believes Japan’s whaling industry is necessary in our modernizing world. Broadly titled, The Truth Behind the Whaling Dispute, Komatsu makes many claims that Japan needs to curtail certain whale populations to prevent other fish species from going extinct, and that these animals are just “part of the food chain”.

Komatsu’s basic point is that after a certain amount of years protecting the whales, we reach a point where whales will start competing with human fisheries and make the major human-consumed fish species go extinct—(Editor’s note: Like Bluefin Tuna perhaps? Damn those whales. They’re ruining our sushi menus).

The only problem with that theory is most whale species don’t eat fish targeted by humans. Minke and baleen whales eat krill, while sperm whales mainly eat deep-sea squid that are unreachable and undesired by fishermen.

What I think does ring true in Komatsu’s argument is his depiction of anti-whalers as having an unflinching belief that whales should be protected because of how big and majestic they are. Unlike whales, one can travel the countryside to see pigs, cows and chickens packed by the thousands into cramped stockyards, yet there is a much more ubiquitous support for “save the whales” than “save all farm animals”. His underlying point is that because we have overprotected some whales since their closest chance of extinction in the 1960s, we as humans need to play the role of god and control the populations of certain whale species that may overtake others. According to Komatsu, it’s not as easy as letting nature restore itself:

“Misunderstanding leads the ignorant public to believe that the ‘leaving whales alone’ doctrine is the correct approach to restore proper balance in the ecosystem,” Komatsu says. “It is completely wrong to believe that ocean resources can recover to the virgin status, if left alone.”

Komatsu’s example of this is antartica’s blue whale population, which dropped from 200,000 to 500 whales in the 1960s, and since then has risen back up to 1,200. He says the population has not yet reached its original level is because minke whales have been taking all the krill in the Antarctic for themselves. Like the hundreds of movie-depicted time travelers who have to fix the past to restore the present, Komatsu says we need to “cull a considerable number of minke whales.” (Editor’s note: H.G. Wells wrote a book about this right?)

“This is a law of nature with which mankind has interfered,” Komatsu says. “Since mankind has broken the law and skewed the balance of nature, it is a duty imposed upon us to act responsibly and bring it back to the proper balance.”

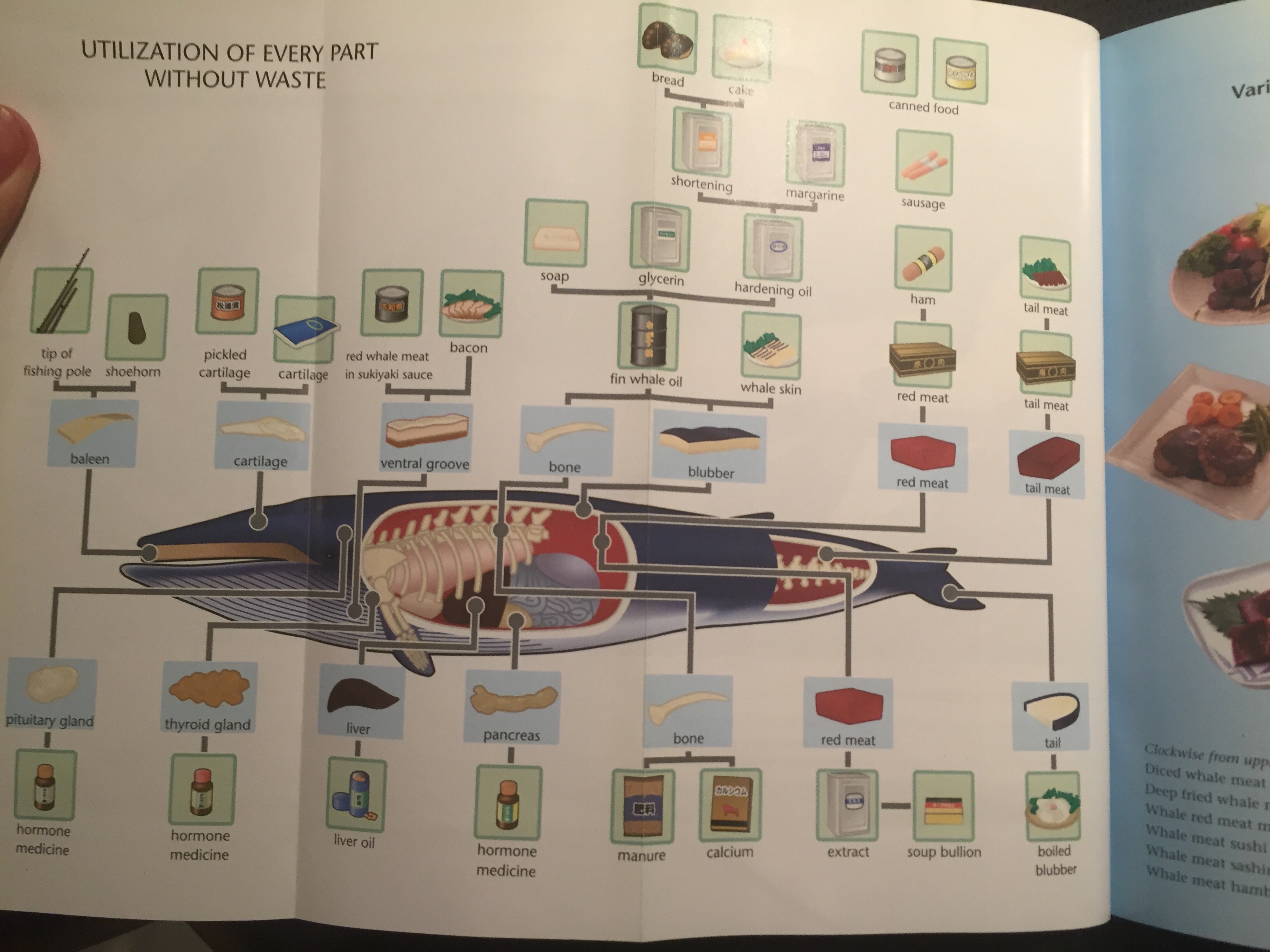

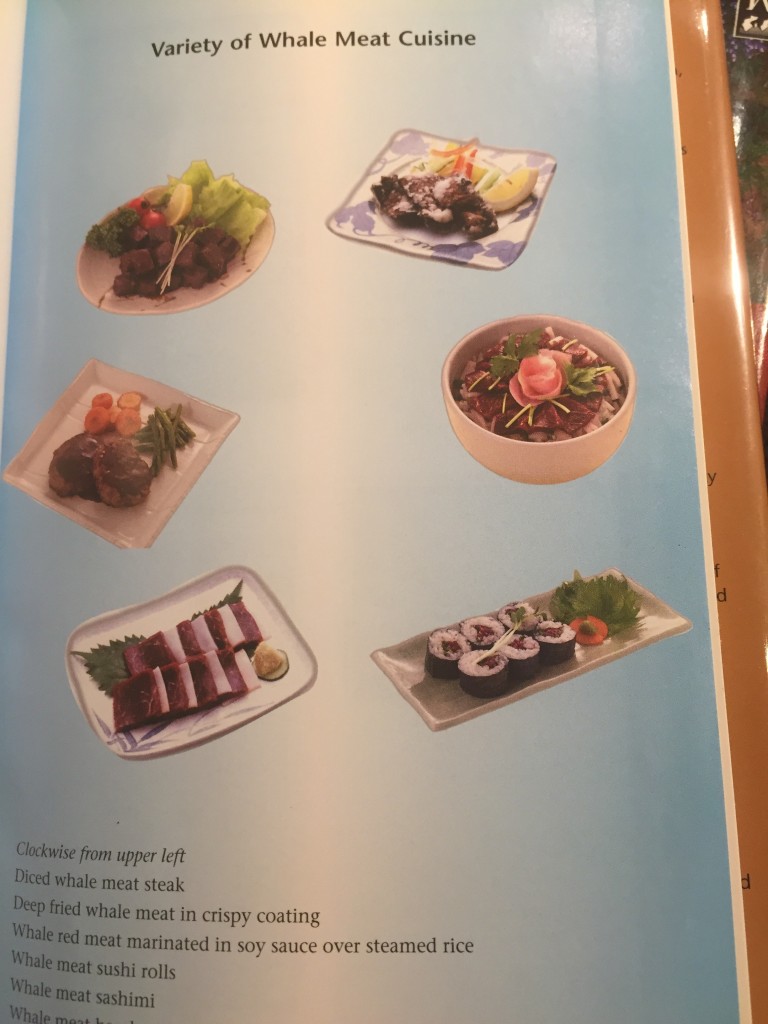

You need to really be invested in this topic to get a lot out of Komatsu’s longwinded, high school-like thesis of a book on why whales need to continue to be hunted. Later sections I haven’t discussed include: 1) why whale meat is an important source of protein that we aren’t utilizing to the fullest 2) why whale meat is more environmentally friendly than beef, which requires deforestation for farmland. Komatsu claims naïve environmentalists are blind to the possibilities of whale meat:

“Which is better for conservation of nature, expansion of grazing land by deforestation or sustainable utilization of a part of wildlife?” Komatsu says. “It would be a folly to discard utilization of renewable resources just for the sake of appeasing so-called environmentalists whose egotistic assertion have been disseminated through misleading TV commercials.”

I suppose we never know at what point in the near future we’ll have to stop eating beef to preserve the planet. I heard from one Japanese friend that good whale meat can be quite tasty. Komatsu argues that soon, when humans will be totaling more than 10 billion, it will be hard to keep up beef and chicken farming—since that accelerates global warming by cutting down trees for land. The excrement from farm animals pollute the water and kill off natural water plants and freshwater fish.

“Under these circumstances, can we afford to abandon the idea of utilization of whale resources? The answer is: ‘Absolutely not!'”

On the topic of the Japanese using whales as an important source of protein, Komatsu lashes out at the IWC (which he later brands as “Goblins” for shifting the original focus from “stabilizing whale oil prices” to a focus on protecting whales) by saying they totally disrespect the cultural traditions of places in Africa and Asia. He says urban civilians are fooled by environmentalists handing out pamphlets showing gorillas being eaten by essentially countering with thought ‘well, what if they’re not eating an unreasonable amount of gorillas!’ In his actual words:

“The arrogance of their assertion, ‘stop eating wild animals’ totally disregards the social structure of the people surviving on the meat of hunted animals.”

Komatsu might be right in thinking environmentalists are pushing us towards adopting developed countries’ more boring diets, food being one of the things that helps tie Japan to third world countries that offer similarly diverse foods. You can be sure in the 1960s there weren’t as many crustless, paper-white bread sandwiches at konbinis as there are nowadays, leading Komatsu to this fear of Japan being stripped of its whaling cuisine (despite the fact not many Japanese eat whale anymore. (Editor’s note: The Japanese government has over two tons of frozen whale-meat, much of it from ‘research’ whaling that it’s saving for some unspecified emergency. Whaling may not sustainable without Japanese government subsidies which begs the question—should taxpayer money be used to sustain it and do most of the Japanese people want public funds used for that purpose). As an American, I can definitely agree the internet has led to a stigma that certain foods such as Natto have been framed too negatively, and in Komatsu’s eyes I suppose whales are no different.

“No one has a right to criticize the food culture of other people. When we Japanese eat our food such as NATTO (fermented soy beans), ANKO (sweetened black beans) and SASHIMI (fresh slices of raw fish), we accept that some people may think that such food is weird (it is theit business to think so), but we would be angry if they forced us to stop eating it.”

Movies such as The Cove are able to post generally agreed ‘disturbing’ pictures of whales (and dolphins) being sliced apart, but Komatsu raises the question of “Why is it more disturbing than pig and cow slaughter houses?”

As my friend and Johns Hopkins Asian Studies Professor Yulia Frumer points out, Japan relies very heavily on foreign exports and likely harbors ill feelings for having to listen to the U.S. for what foods it can and cannot receive. I admit that Komatsu gives dozens of faulty numbers in his writing about whales, (he actually hindered his argument in “The History and Science of Whales” by mistakenly saying the estimated number of sperm whales was 200,000 when it was actually 2 million,) but I think it’s important we consider how some of Japan’s older generations feel belittled by the U.S. and Australian whaling/fishing commissions that wants to tell them what they’re allowed to catch.

“Analysis of their argument leads us to believe that they are viewing the rights of the non- human creatures as equal to the rights of men. Here, I think it is worthwhile to ponder upon what truly should be the protection of animals.”

Komatsu manages to make some logical arguments but there is a twisted logic to it and in the end, whaling in Japan is not necessarily something that the majority of the population wants and the industry is unsustainable.

So why does it keep getting funded? That’s a subject worthy of a book in itself.

Jake Adelstein contributed to this review. For more on the whaling issue please see this article originally published in The Daily Beast.