Mr. Takahiko Inoue, buddhist priest and yakuza boss passed away in February last year. In order for those who can’t read English but knew him or would like to know about him, I’ve written his obituary in Japanese below (日本語の弔い記事は一番下にあります). I hope that those who read it will be able to understand that even amongst the yakuza, there are some good people–in their own way.

Takahiko Inoue, yakuza boss and Buddhist priest, died Feb. 10 at age 65. The police determined that he fell from the seventh story of the building where his office was located. When the ambulance arrived, Inoue told the crew: “I’m fine. Just take me to the hospital. I’ll walk to the car myself.” Those were his last words. There was no protracted investigation.

Those who knew him, in the underworld and in normal society, referred to Inoue as “Hotoke” or “The Buddha.” “Hotoke” is also police slang for “the dead.” One of his friends sadly joked after his death, “Well, he finally became a real Buddha, after all.”

It’s not uncommon for a disgraced yakuza boss to seek refuge by becoming a priest after banishment; but it’s usually just an exchange of Armani suits for robes and tax-exempt status. Sometimes, the robes double as a sort of bulletproof vest, because even in Japan, it’s bad PR to kill a priest. However, bosses who are practicing Buddhist priests? Rare.

Inoue was a rare breed. The yakuza, for all their talk of being humanitarian groups, are generally vile parasites on Japanese society. The modern yakuza make their money from extortion, racketeering, bid-rigging and fraud. Inoue was different; a holdover from an older generation. At the time of his death, he was the leader of a 150-man group in Shinjuku, and one of the top yakuza in the Inagawa-kai, Japan’s third-largest organized crime group.

Inoue was born in the city of Kumamoto in 1947. In his 20s, he came to Kanto, worked on the docks and eventually joined the Yokosuka Ikka, a once-powerful faction of the Inagawa-kai that was originally an independent federation of gamblers. He served for many years as the personal bodyguard of Susumu Ishii, the head of Yokusuka Ikka. Mr. Ishii eventually became the second-generation leader of the Inagawa-kai. Because of his financial savvy, he was known as the father of the economic yakuza.

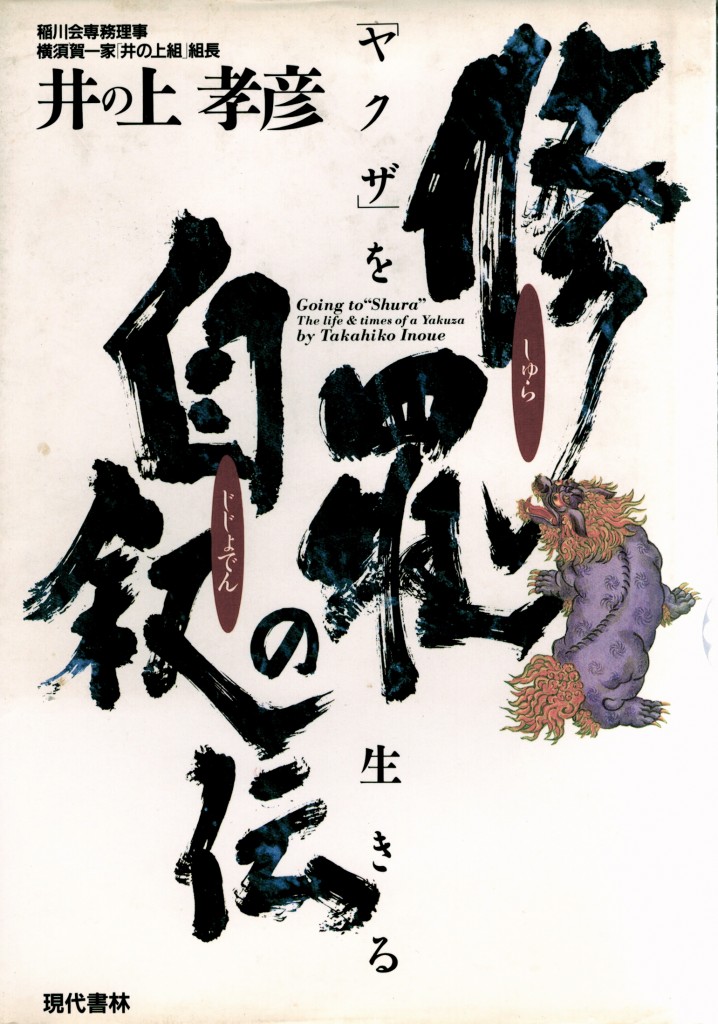

Inoue was hot-tempered in his youth and went to jail for attempted extortion and other crimes. His nickname used to be “Oni no Inoue”— the Demon Inoue. During his time in prison, he became familiar with Buddhism and eventually became a Buddhist priest, yet remained a yakuza boss as well. Inoue justified his decision this way: “It’s easy to give up on the delinquents of the world, but if I give up on them who will make them better people? Who will teach them discipline?” He wrote the story of his life and what he believed in “Going To Shura: The Life and Times of a Yakuza,” published in 1996.

He reconciled the two realms as follows. Buddhism has its rules. The Inoue-gumi had its rules, taken from the Inagawa-kai Yokosuka-Ikka. Inoue worked to uphold them both. In some places, they actually overlap. The Inoue-gumi rules forbid: 1) using or selling drugs, 2) theft, 3) robbery, 4) sexual misconduct, 5) anything else that would be shameful under ninkyodo, the humanitarian way.

To become a Buddhist priest like Inoue, you have to follow 10 grave precepts. Do not: kill, steal, engage in sexual misconduct, lie, drink or cloud the mind, criticize others, praise oneself and slander others, be greedy, give way to anger or disparage the noble path.

Hotoke was not very good about avoiding alcohol, but who is in Japan? He was a gambler as well — but an honest one. When it came to running the organization, he was an absolutely strict enforcer of the prohibition on drugs. Several years ago, when he found one of his own members dealing in methamphetamines, he banished him from the organization immediately. His group gave up collecting debts and loan-sharking years ago. They stopped collecting protection money even when it was offered. One local bar owner and former patron said, “Inoue never asked for more than we gave, and he was there when we needed him. Better and cheaper than SECOM.”

A former police chief who knew Inoue personally said on background: “I can’t openly praise the yakuza, but he didn’t cause trouble; he wasn’t involved in fraud, drugs or extortion. He kept his crew in line and he helped keep the peace. He was an asset to Kabuki-cho, an area where any sort of morality is in short supply. He had standards.”

I can’t say Inoue and I were close friends. We exchanged books on Buddhism and good wine. He was a wine aficionado; he sent me imo-shochu — potato hooch — from his hometown. (It gave me the worst hangover of my life.) He was always the teacher and I was the student. I didn’t have much to teach him.

I felt I knew him before we’d even met. In the early ’90s, my mentor, Detective Chiaki Sekiguchi of the Saitama Police Department, recommended Inoue’s autobiography to me as “a good introduction to the yakuza, how they used to be, why they are tolerated, and how they will never be again.” By the time I actually spoke to Inoue, Sekiguchi was a hotoke himself. Cancer.

Inoue was one of the first generations of yakuza to move from outlaw to law-abiding businessman. He was a smart investor, running restaurants, allegedly owning over 10 buildings, taking in legitimate revenue to keep his organization together. He followed the advice of his former boss. Mr. Ishii once told him, “Be a yakuza that pays taxes.” He paid taxes; he was generous with his wealth. He made charitable donations quietly and without great fanfare.

Inoue understood that the yakuza world was changing for the worse and that he was out of date. In his autobiography he wrote, “Yakuza unable to collect traditional revenue are turning to drugs; they’ll do anything to make money, even rob each other.” He wanted to return the yakuza world to its ideals but realized that all he could do was “make sure my group follows the rules and make them understand that we are all judged and eventually pay for what we do. The universe has its karma police.”

I wish that were true. Sometimes, it seems like the karma police are on strike in this realm.

There’s a saying in Japanese: “Jigoku ni Hotoke (To meet the Buddha in hell).” It refers to the good fortune of finding an ally in the worst of circumstances. Considering how I’ve lived my life so far, I hope it applies to the metaphysical world. I hope The Buddha comes to visit me on the other side. I’ll need some help in making my jailbreak.

井の上孝彦稲川会横須賀一家井の上組組長・現役の僧侶が2月10日、他界しました。65歳でした。警視庁が調べたところ、井の上さんは、井の上組事務所があるビルの7階から転落したと断定した。救急車が現場に到着した際、井の上さんは救急隊員に対して「大丈夫だ」と最後の言葉を残したという。捜査本部は立っていなかった。

井の上さんは裏社会でも表社会でも「仏 (ほとけ)」(Buddha)として親しく呼ばれた。警察用語では、「仏」は「死人」という意味もある。彼の死を知った知人は「いよいよ本当に身も心も仏様になりましたね」と肩を落としながら弔いの言葉を述べた。

大失敗したヤクザのボス、または破門された幹部は逃亡先として僧侶職に就くことはそれほど珍しくない。しかし、それはあくまでも稼業の背広を袈裟に切り替える行為で、しかも税金対策。また、僧侶の袈裟を防弾チョッキに代用することもある。現代の日本でも、お坊さんの殺害は御法度で、広報の面では好ましくないから。しかし、組長を務めながら僧侶に励むヤクザは稀にない存在。

井の上さんは希少動物のようだった。「任侠団体」と唱える暴力団の大半は社会の寄生虫に過ぎない。現代のヤクザは恐喝・談合・総会屋めいた行為・詐欺などが稼業。井の上さんは一昔世代のヤクザだった。死去の際、新宿で150人体制の組織を牛耳った。日本で3番目大きい暴力団「稲川会」の最高幹部でも務めていた。

井の上さんは1947年、熊本市で生まれた。20歳代、関東へ行き、港などで働き、稲川会の名門だった横須賀一家に入り。横須賀一家はそもそも双愛会系列の一本組織だった。井の上さんは横須賀一家のトップだった稲川会二代目会長の石井隆匡会長のボディガードを数年間務めた。経済に詳しい石井会長は「経済ヤクザ」の先駆者とも言われた。

井の上さんは若き頃、多血漢で、恐喝未遂などで懲役もあり、昔のあだ名は「鬼の井の上」だったという。懲役を繰り返すうち、仏教を知るようになり、僧侶となった。僧侶と組長の任務を両立した。彼の生き方は「世の中の不良を見捨てるのが簡単なことだが、僕は彼らを見捨ててしまったら、誰があいつらを善人に育てるのか。誰が懲らしめてやるのか」と正当化。彼の人生と信仰を修羅の自叙伝・「ヤクザ」を生きるという1996年の本(出版・現代書林)で述べた。

井の上さんは極道と六道の間に生きていた。

仏教は掟がある。井の上組も掟がある。(井の上組の掟は横須賀一家の掟)。双方の掟は重なる部分もある。井の上組は禁止していたことは次の通りです。①薬物の使用・売買②窃盗③強盗④破廉恥な行動⑤任侠道に反する行為

僧侶は厳重十誡を守らなくてはならない。

殺してはならない。

盗んではならない。

淫らなことをしてはならない。

・悟ったと嘘をついてはならない。

・酒を売って(買って)はならない。

・他人の間違いや欠点をあげつらってはならない。

・自らをほめ、他をそしってはならない。

・物心両面にわたり、他に施すことを惜しんではならない。

・怒りを抱き、自分を失ってはならない。他人の謝罪を容れる。

・仏法僧の三宝を謗り、不信の念を発してはならない。

「仏」は酒を避けるのが苦手でしたが、果たして日本社会で酒を避けられる人がいるだろうか。博徒でもいたが、如何様はやらなかった。薬物の厳禁を貫いた。数年前、薬物を売買した組員の存在を知り、即座に破門した。井の上組は数年前から取り立てや闇金融から手も引いた。かすり(用心棒代)の収集も取りやめた。近くの飲食店経営者は「井の上さんは、我々が自ら出した用心棒代以上金銭を求めることもなく、助けが必要だった時は必ずやってきました。セコムより安くてサービスが良かった」と振り返る。

井の上さんの知人だった元警察幹部は匿名という条件で「公にヤクザは褒められないが、彼は問題を起こすこともなく、詐欺・薬物・恐喝もやらなかった。自分の組員を礼儀正しくさせたし、治安維持に貢献した。歌舞伎町という倫理欠如の町では、彼は倫理観もあった」

僕と井の上さんは親しい友人と言えない。仏教関連本やワインの交換はしたけど。彼はワインの通でした。僕に地元の芋焼酎を送ってくれた。(実はその芋焼酎が人生最悪の二日酔いの原因となったが…)。彼は先生役で、僕は弟子役。僕が彼に教えることはなかった。

井の上さんと会う前にも会ったかのような感じもした。90年代、恩師の関口千秋刑事(埼玉県警)が井の上さんの自伝を薦めた。「これはヤクザへの入門書としては最高。昔のヤクザを描き、日本社会で寛容されている背景も説明しているし、二度と戻らない真の任侠団体の時代も伝える」と本を褒めた。残念なことに、井の上さんとやっと出会った時、関口さんも「仏」でした。癌。

井の上さんは違法な資金源獲得活動を合法事業へ着替えたヤクザとしては先駆者の一人だった。投資家として才能もあり、複数のレストランを経営して十数軒の建物も所有していたと言われている。合法的経済活動で組織を支えた。石井会長の名言「税金を払うヤクザになれ」を肝に銘じていた。彼は税金を納め、気前が良くて黙々と慈善事業にも献金したのだ。

井の上さんはヤクザの世界が悪化している事情もわかった。自伝では「伝統的な凌ぎを失ったヤクザは稼ぐために麻薬売買でもなんでもやるようになった。ヤクザ同士から金を奪い取るヤクザでもいる」と嘆いた。原点に戻ってヤクザ社会を叩き直そうとしたかったが、「自分の組織をしっかり管理して悪さしないようにするのが私の務めです。彼らに因果応報を悟らせなくてはいけない。兵隊には、六道にはカルマポリース(勧善懲悪警察隊)みたいなものがいると叩き込んでいる」という。

勧善懲悪が世の中の原理だったら、いいけどね。「勧善懲悪の警察隊」がずっとストという気もするけどね。取り締まりが緩い。

「地獄に仏」という慣用句が日本語にある。苦境で頼もしい人や友人に出会うことの例え。自分の人生を振り返ってみると、その慣用句が事実であってほしいのだ。あの世へ行ったら、「仏」に会いたい。僕の脱獄には仏の助けが必要かもしれない。

合掌。

I guess two questions come to mind. Was he helped over the balcony or ledge? I realize its bad press to kill a priest, but like you said the Yakuza has evolved and Japanese society like American society has become more secular.

The second thing is at what point do you stop being considered a Yakuza group, because it seems to me that he and his group stopped being Yakuza when they stopped doing illegal things.

plunging to death from building where his office’s there… it’s hard to beleave however it could be the correct one though, “http://bit.ly/ZdRTvQ”…

how’s it stated by the police as to whether it could be suicide or murder or merely an accident without any case?

Thank you for your sincere reply. I get the point. Anyway, May his soul rest in peace and I wish I knew what to say to the deceased’s family and the KUMI’s henchmen…

Thank you for your sincere reply. I get the point. Anyway, May his soul rest in peace and I wish I knew what to say to the deceased’s family and the KUMI’s henchmen…

Kudos för medryckande och superbra läsning