I was one of those people who wept over Hillary Clinton’s farewell “glass ceiling” speech, and not just because of how the election turned out. It seemed that however way you sliced it, women will have a hard time in the workplace and in modern society and that Clinton’s defeat was symptomatic of a huge, cancerous issue. Sob.

Here on the archipelago, we’re feeling the sharp edge of the blade known as overwork, afflicting both women AND men as they struggle to keep up with the increasingly ruthless culture of corporate Japan. The recent suicide of a 25-year old woman who worked for ad giant Dentsu is just the tip of the iceberg of a phenomenon known as “black companies,” or companies who enforce long working hours and excessive work ethics. This double duty can result in stress-related illnesses, severe depression and worse. In the case of this 25-year old, much worse. Just before her death, the texted her mother that she couldn’t stand work and she couldn’t bear life.

On the other hand, most Japanese – white collar or not, are well aware that clocking in over 100 hours of overtime a month is quite common, and so is not getting paid for that time. Dentsu was raided by Labor ministry investigators earlier this month, and they raked up evidence to show that workers were actually falsifying their overtime records to avoid having to bill the company and cause trouble. Such a mind-set can only exist in a country like Japan, whose finest moment came in the 1970s to 1980s, during the miraculous economic growth period. This was when trading companies gobbled up Manhattan property and car manufacturers kicked Detroit’s ass and a Harvard professor wrote a book called “Japan As No.1.”

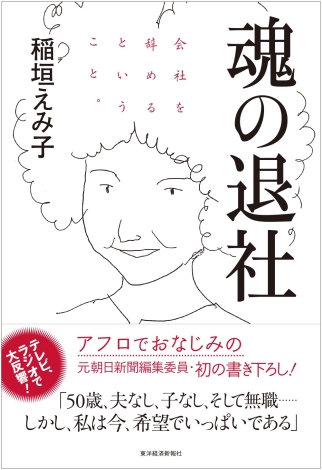

“That was the rosiest time in post-war Japanese history,” writes Emiko Inagaki in her bestselling autobiography “Tamashiino Taisha (My Soul Wanted to Quit).” She adds that Japan’s current horrendous work culture that puzzles and even disgusts the rest of the world, is a holdover from that rosy time. “No one has come up with a dream to quite match the dream of the rapid growth era. Working hard and shopping with the money earned and then working hard some more and shopping some more – we loved it. We still love it, and refuse to look for an alternative.”

Inagaki is a former journalist for national news conglomerate Asahi Shimbun, and her book tells how she climbed up Asahi’s mercilessly patriarchal hierarchy rung by bloody rung. The media is the one place in the Japanese corporate world where a woman can even hope to compete with men in the same arena, and according to Inagaki she chose the profession for that very reason. A graduate from one of the nation’s top universities, Inagaki felt that she owed it to herself and her family, to become a financially independent individual. Other women of her generation were apt to work for a few years, get married and withdraw into the home. But for 3 decades, Inagaki plugged away at the job, moving from one department to another, one regional office to another. For the most part, it was a ride. In the book, she writes with loving tribute to the years she gave to Asahi, years that shaped her personality and cemented her resolve.

On the flip side, she was often depressed and prone to binge-shopping. She writes with comic flair of how, on every payday she would sail into her favorite boutiques and pick armloads of posh outfits that she subsequently never wore, how she was turned on by the gushing welcome she got from the salesgirls (“after all, I was an excellent customer!”), basking in the euphoria of buying just about anything she wanted. And it wasn’t just clothing. She loved getting drunk with colleagues and friends at expensive sushi restaurants. She loved riding cabs everywhere. And she was proud of being able to afford the rent on a designer condo when other women her age were struggling to pay for their kids’ school fees. Inagaki was living the Japanese Dream – work like crazy, spend accordingly and to hell with everything else.

At a certain point though, she had to ask herself if this was true happiness. The answer was an uneasy NO. And then Lehman Shock came along in 2008 and partially jolted her out of the earn-spend cycle. “But what really did it for me was 3.11,” she writes. “I vowed to stop spending so much on myself, and I especially wanted to cut down on utility bills.” Inagaki covered Fukushima’s nuclear meltdown, and witnessed first hand the potential side effects of unbridled economic progress. “The Japanese were apt to think that working and earning was the most important priority. But 3.11 showed us that there’s more to life than that, and the revelation can come at any time.” Inagaki decided to use as little electricity as possible, just as a personal experiment. “I would come home, and not turn on the light switch and wait until my eyes got used to the dark.” Pretty soon, she could navigate her way around her home with no lights at all. “I thought: so this is what being truly independent is all about.”

Gradually, the idea dawned on Inagaki that she was free to quit the company. “I had been working for Asahi for 30 years. The idea of leaving scared me a little but more than that, I was exhilarated. Dare I do it? Would I be able to survive?” At this point, Inagaki was 50 years old and single, with nothing to her name but a position in a highly respected company. To cut herself off from this veritable life support system, in a country renowned for discrimination of women (especially unemployed single women) could spell disaster. She wasn’t going out there completely unequipped. Prior to her leaving Asahi, Inagaki had her hair done – in a stylish afro. And she had already weaned herself off the expensive lifestyle and started looking for a smaller, older, much cheaper apartment. She was KonMariing her stuff as well. Out went the expensive, unworn outfits. The designer furniture and decor items. One by one, she pared herself down and came to recognize who she really was, shorn of the invisible corporate armor that had both protected and incarcerated her.

Inagaki now works as an occasional TV commentator and takes on freelance writing assignments. The latter as she writes in the book, pays so little it took her breath away. Back in Asahi, she had been convinced that professional writing was a fairly lucrative gig, but the reality of being an independent freelancer has hit her hard. Still, with no dependants and a cheerful disposition, she can treat her new life as one on-going adventure. She cooks her own food, hand washes her laundry, has no A/C and generally keeps expenses down to about 100,000 yen a month. To her surprise and delight, she is suddenly enormously popular with men of all ages. “Everyone wants to talk to me. The other day, a young photographer asked to take my picture.” She attributes it to the afro and her new, carefree aura. “If there’s any hope for us, it’s to believe that it’s okay to live as an individual, to liberate yourself from working for a company.” With so many Japanese convinced that life begins and ends in an office, her message is vital – a shining light glimpsed at the end of a long, dark tunnel.

When your soul wants to quit, well, it’s time

[…] Source: Japan Subculture Research Center […]

She sounds like an amazing woman.