Japan plans to restart its troubled nuclear fuel reprocessing facility, Rokkasho (六ヶ所再処理工場) in October of this year, but is that a good idea? Experts say Japan should simply shutter its nuclear reprocessing plants & avoid making more dangerous plutonium. Why doesn’t this happen? We decided to see if we could explain. Here is our short primer on the nuclear fuel cycle follies of the land of the rising sun.

Why do most nuclear power dependent countries including Japan want to reprocess spent nuclear fuel?

This is a very good question. If you have no idea what reprocessing nuclear fuel is all about, please hold on. We’ll get to that. Let’s talk a little bit about nuclear plants in general.

Guess what? Building a nuclear power plant on a volcanic island isn’t a good idea. In fact, it’s probably very dangerous and stupid. This is the conclusion the island nation of Taiwan reached last week. Taiwan’s government said on Thursday it would seal off a nuclear power plant due to open next year. The public has repeatedly criticized the plant as unsafe, and it will be shut for three years, at a cost of nearly 162 million dollars, pending a referendum on its future.

Meanwhile, under Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, Japan is rushing to restart its nuclear reactors (despite widespread opposition) and plans to reopen the dysfunctional Rokkasho Nuclear Reprocessing Facility in October. Japan’s plans to have a self-perpetuating nuclear fuel cycle have been a colossal & expensive failure—and the Rokkasho facility (as well as many other nuclear facilities) pose a serious threat to the safety of those living near them and possibly the rest of the world. Japan’s nuclear security is poor at best and the workers are not screened making them a potential target for terrorists.

Mr. Frank von Hippel, Professor Emeritus of Princeton University, and Mr. Klaus Janberg, former CEO of a German nuclear service company and nuclear advisor, told reporters in Tokyo last month that storage of spent nuclear fuel should be an alternative to the reopening of the Rokkasho Spent Nuclear Fuel Reprocessing Plant operational this year. Mr. Hippel is the former Assistant Director for National Security in the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy. He advised the Clinton White House on aspects of the joint U.S.-Russian non-proliferation programs.

As mentioned above, Japan’s nuclear reprocessing plant is planned to finally start running by this October, after more than 20 years of disastrous attempts to make it work. In July of this year, the two nuclear experts proposed to the Japanese government, including the Foreign Ministry and METI (Ministry of Economy Trade and Industry) officials that it would be advisable to install dry cask spent fuel storage units at nuclear power plants sites and elsewhere to prevent the Rokkasho reprocessing plant from generating plutonium that would further increase Japan’s excess stock. They said their proposal could help implement possible alternatives to Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s commitment made at this year’s March Nuclear Security Summit at The Hague not to possess plutonium reserves without specified purposes. Abe pledged to minimize stocks of separated plutonium by matching supply and demand.

The two experts spoke at the FCCJ on July 1st about Nuclear Security and Reprocessing: Spent Nuclear Fuel Storage Option & an Alternative to the Rokkasho Reprocessing Plant. We have summarized the Q & A below, adding exposition where we felt it was needed.

Klaus Janberg (right), Former CEO of Gesellschaft für Nuklear Service, experts in the nuclear industry say Japan should leave Rokkasho nuclear fuel reprocessing plant shut and store nuclear waste.

Why do most nuclear power dependent countries including Japan want to reprocess spent nuclear fuel?

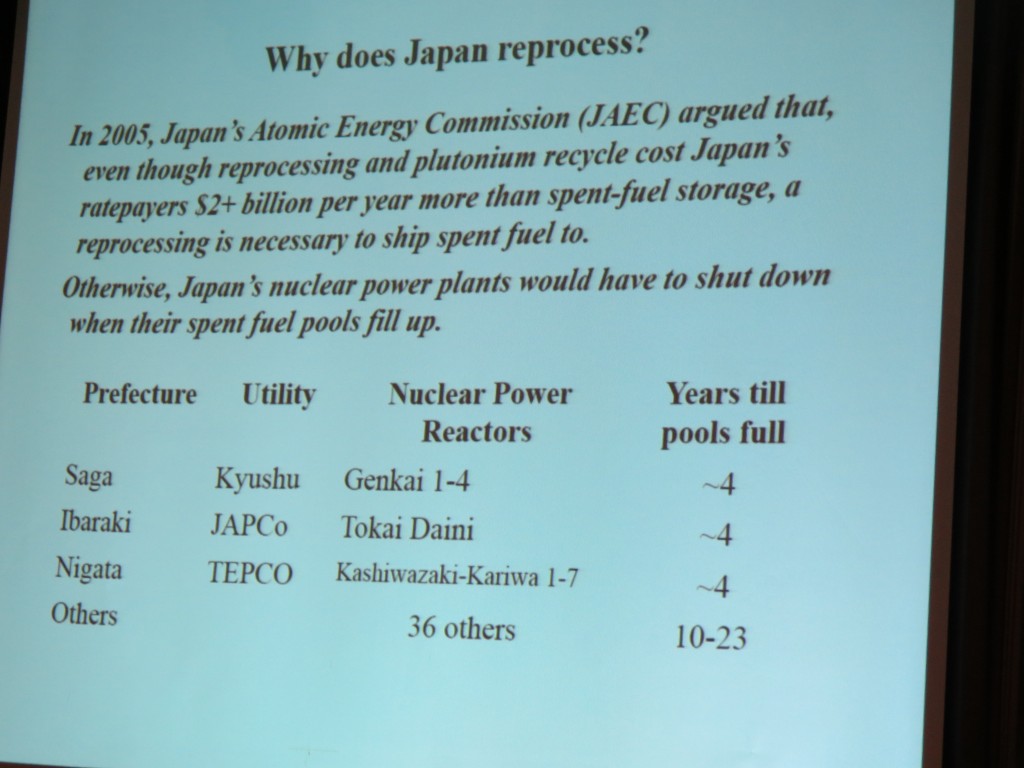

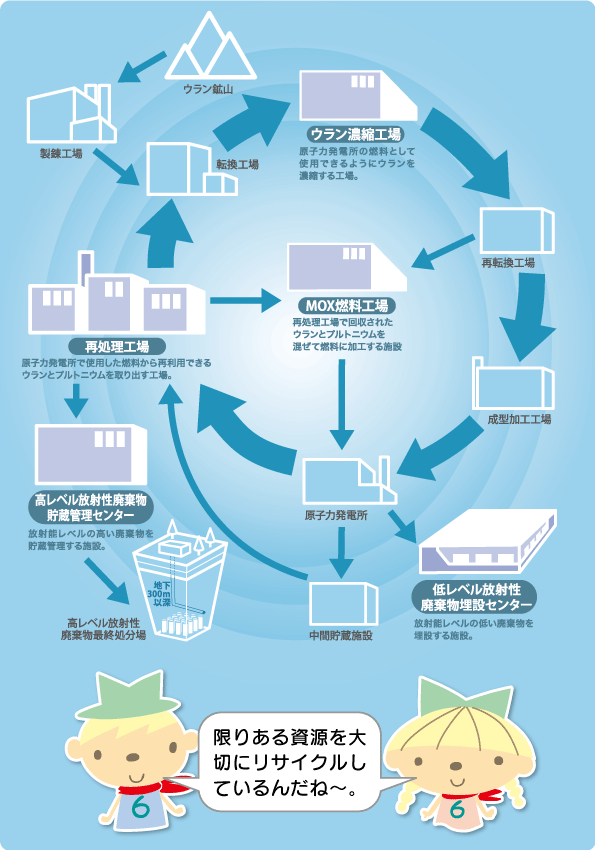

The Rokkasho plutonium plant was built to end Japan’s dependence on imported uranium, oil, gas and coal. Most countries started civilian reprocessing to acquire plutonium breeder reactors, like the Monju breeder reactor, in Japan. It turned out that such reactors are much more expensive and much less reliable than water-cooling reactors. Currently, the argument in Japan is that spent fuel pools are filling up and it is necessary to have a place where to send the spent fuel. Rokkasho is the only place.

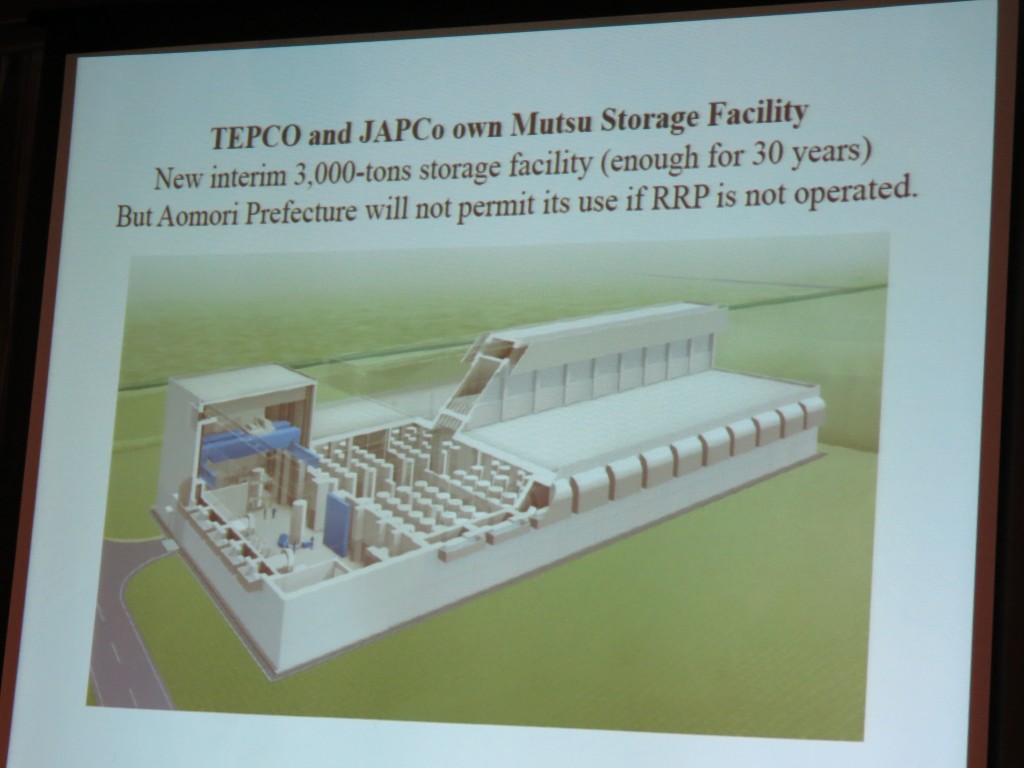

“TEPCO and KEPCO (Kansai Electric Power Company) built and completed in Mutsu city, in Aomori Prefecture, a spent fuel storage facility, which would be much enough for storing the spent fuel but Aomori, which also hosts the Rokkasho reprocessing plant is reluctant to use the storage facility unless the reprocessing plans begins,” says Frank von Hippel, He explained it was a political problem rather than a technological problem.

Several countries like the UK an the US have also tried to operate plutonium “breeder” programs but abandoned them after several accidents occurred and because they have come to the conclusion that it was not economically feasible. They are now struggling with what to do with the tons of leftover plutonium.

Japan is the last state without nuclear weapons to still reprocess spent nuclear fuel.

Japanese officials also know how costly it is to continue the project that started almost thirty years ago. But why do they insist continuing the process?

“Keep the zombie alive”

Why does Japan cling to its spent nuclear fuel reprocessing program despite all the economic and technical problems?

Japan cannot stop its nuclear fuel cycle plans because the Japanese government has an agreement with Aomori Prefecture, where the Rokkasho plant (located in Rokkasho village) was built. If they can’t reprocess the spent fuel stored there, Aomori Prefecture will remove it immediately. According to high Japanese government officials, the agreement is equivalent to an international treaty, therefore it cannot be turned over. Besides, Japan has nowhere else to move away the fuel. And which country in the world outside of Japan could ever take it? Right now, all the spent nuclear fuel (使用済み核燃料) stored at Japan’s nuclear facilities, on the assumption that it can be reprocessed, is counted as an asset by the power companies.

If Japan abandons its nuclear fuel cycle plans, the “asset” would become a huge liability and every single electric power company would become insolvent. In other words, as long as the pipe-dream of nuclear fuel reprocessing is government policy, the nuclear waste itself— is an asset; it has value. But if the stored fuel is found to have no value, than the fuel and the costs of storing it–all of this become a liability. If this were to happen, TEPCO, (Tokyo Electric Power Company) is already a de facto insolvent entity. The so-called nuclear village insists that this would be disastrous for the Japanese economy.

The current administration wants to make sure Rokkasho is ready to go and restart reactors to keep TEPCO alive. If TEPCO has another fiscal period where they are in the red, banks will stop lending them money. Restarting the reactors is one way to keep the TEPCO zombie alive.

Now, you may counter by saying, “Hey didn’t TEPCO make 4 billion dollars last year?” Yes, well part of that was a gift from the Abe government which agreed to pick up 47 billion yen (That’s $458,134,380) worth of cleanup costs for the water leaking out of Fukushima—because TEPCO was doing such a lousy job. Okay, well, 3.5 billion is still a great profit. And TEPCO will stay in the black—just as long as nuclear waste is considered an asset.

Some current and former U.S. officials said they expect Japanese officials will abandon their plutonium fuel program once they realize how much it will cost. But it isn’t happening.

The US has been building a MOX plant for its excess weapon plutonium, it was supposed to be operating in 2007 but experts are now saying it can start by 2020. But it has become so expensive that the Obama Administration is talking about abandoning the project and trying to find another cheaper way to the plutonium disposal management.

But for Japan, which is supposed to be a country of honor and promises kept, it is very unlikely. Reportedly, Prime Minister Takeo Fukuda in 1977 called the program’s promise of energy independence a “life and death” issue, and that attitude persists at the highest level of the Japanese government.

“It is in the Japanese mentality to never go back after they made an agreement,” a prominent anti-nuclear activist and attorney told JSRC when discussing the agreements in place that keep Aomori’s Rokkasho plant alive.

How safe is the Rokkasho plant from terrorism? The IAEA (International Atomic Energy Agency) is formerly responsible for ensuring that plutonium does not get removed from the Rokkasho plant by a third party, how accurate is the system installed there since it is going to start operating this October?

The measures and accuracies for the IAEA checks that plutonium won’t leak from the plant is of about 1%. If operating at full capacity, it would separate about 8 thousand kg of plutonium per year. Therefore 1% accuracy is about 80kg. The IAEA considers 8kg is enough to make a nuclear weapon. In other words, if the 1% not accounted for was actually stolen, it would be enough material to produce the equivalent of 10 nuclear weapons in a year. The IAEA recognizes that that’s not good enough, and added a system they called “surveillance and containment,” to monitor all the doors to ensure the plutonium could not be stolen.

“I don’t know about Rokkasho. The problem is that there is no way to check within the accuracy measurement that everything is still there. Reprocessing is recognized as a serious problem for safeguards and for these reasons, even though the IAEA spends globally 20% of its safeguard budget on Rokkasho and Tokaimura, it is recognized as being a hugely costly operation,” Frank von Hippel explained.

The US spends about a billion us dollars a year for the security of nuclear materials. Even so, the US still has some problems. Last year, an 82 year-old nun reportedly penetrated the security system and went to the central part of a nuclear facility. There is no perfect security. “The only perfect security is to not have the nuclear material in the first place.” Von Hippel said. “If you aren’t making nuclear weapons, I’d argue that nobody needs to have the nuclear material that could be used to build them.” (Of course, some would argue that Japan wants plutonium precisely for those reasons.)

Final disposal of the spent nuclear fuel: at which stage is the nuclear material less harmful?

The fuel is the most dangerous when it’s in the reactor, becomes less dangerous when it goes into a pool, even less dangerous when it goes into a cask, and least dangerous when the cask is buried deep underground. The two countries that understood that it isn’t in their best interests to keep the spent fuel on the surface of the earth forever are Sweden and Finland. The issue in Japan may be the suitability of the geological situation of the country. Those casks that contains spent fuel elements under helium that keeps the fuel intact—they can keep the fuel for about 38 or 39 years.

Why do the power companies not want to abandon nuclear power?

Nihon Gennen, the company which owns the Rokkasho plant, is currently bearing a huge debt for the construction of the Rokkasho reprocessing plant, and the electric power companies are guaranteeing/insuring this debt. The current law states that the money to pay back the debt with the fund raised by the consumers can’t be used if the Rokkasho reprocessing plant is not running. The moment you say that you stop the Rokkasho reprocessing plant, Nihon Gennen will go bankrupt. And the debt will be a loss for the electric power companies. The major electric power companies will register a collective loss of about 2 trillion yen and those companies can’t endure this.

Instead of thinking about all these impossible things, Japan believes it will be easier to start running the reprocessing plant. If the reprocessing plant becomes operational, there will be an additional amount of plutonium that will be produced, and that plutonium will be useless without the Monju plant running. In which case the plutonium will have to be burnt with (plutonium thermal use) MOX fuel. And therefore they can’t stop the MOX plant either.

As long as Rokkasho and Monju keep running, the power companies make money—if they are put out of commission, the power companies fail. All the politicians, scholars, ex-bureaucrats, investors and their cronies who are riding the nuclear gravy train will be left out in the cold and suffer losses as well. The so-called costs of nuclear energy do not take into account compensations for disaster, nor the costs of storing nuclear waste for centuries. The cost is only cheap for the power companies—the taxpayers pick up the rest of the bill. The storage facilities for nuclear waste in Japan are nearly full and no one wants to take them.

Kei Shimada, a japanese photographer and director of the documentary movie “Rokkasho Mirai” (2013) told JSRC that at the time under the DPJ, right after the Fukushima nuclear accident, when the cabinet proposed the zeroing out of nuclear power stations in all Japan, the head of Rokkasho village and the city hall members opposed the phasing out of nuclear energy and they repeatedly went to Tokyo to demand the continuation of the nuclear energy policy.

“As for the villagers, there are so many of them who work at the Rokkasho plant, that in case a zero nuclear energy policy in Japan is decided, and in case the Rokkasho plant has to close, they will all lose their jobs. That’s the kind of reaction I heard from the villagers of Rokkasho when the government was walking towards a no nuke policy. Therefore, I think that after the LDP started ruling the country, the people around Rokkasho were happy about the movement to restart the nuclear power plants. But it doesn’t mean that the anxiety has disappeared. I think the people are anxious, but they are also torn between the fact that they will loose their jobs and therefore their living.”

The Rokkasho reprocessing plant is designed to extract metal from spent reactor fuel. If it starts running this time, it will separate more plutonium, despite the fact that Japan already has about 45 tons of it stockpiled in Europe and domestically–enough for more than 5,000 nuclear bombs. The US and the IAEA has continually raised concerns that the lax security at Japan’s nuclear power plants—which do not even run background checks on the workers–and tolerate yakuza (gangsters) working on site–could make them a target for terrorists. However, when we examine the history of mismanagement and incompetence of the utility companies running the plants, it seems the greatest credible nuclear threat of them all is yet another accident.

Notes:

Several JSRC members contributed to this post.

Frank von Hippel is Professor of Public and International Affairs, emeritus and co-chair International Panel on Fissile Materials. He served as Assistant Director for National Security in the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (1994-5). Nuclear consultant Klaus Janberg managed the development and production of the casks at GNS that provide interim storage for spent fuel in Germany and a number of other countries.

[…] Japan Subculture Research Center goes in depth to explain the complex interdependency of Japan’s nuclear reprocessing program and the instability of their nuclear power utilities. http://www.japansubculture.com/the-ides-of-october-japans-nuclear-reprocessing-dream-is-the-worlds-n… […]

Well… Nuclear energy per se is not a bad thing, but the old school reactors we’re using are. They’re dirty, inefficient and dangerous. It would be much preferable if more public resources went into research on nuclear power, because the economics of private sector energy production won’t allow allocation of enough resources to create tangible results fast enough.

The last “era” when a proper amount of resources went into research on nuclear power was in the ’50s-’60s and since then it’s stagnated, so we’re stuck with the basic designs from back then. Consider where building standards, cars or any technology would be, if the same stagnation had happened in that sector. What if nuclear had been allowed to develop as fast as computers?

There are interesting designs being tested at this very moment, but they won’t be reaching the market for another few decades as it stands.

[…] to push restart plans as they struggle to find a way out of the old nuclear program that required them to reprocess massive amounts of nuclear fuel. Backing out of nuclear power also holds the potential for widespread financial failure of the […]

Some gas utilities will offer this inspection service, if not they can offer a list of trusted suppliers. It is also important to ensure that any ventilation is maintained. This would have been established when installed, but any changes will affect the appliances operation. Keep watch over your appliances operation. Signs of problems can be soot buildup around burners or a change in the flames color from blue to yellow.