Today marks the start of The Year Of The Dog. I like dogs and I like them because I think journalists should be the guard dogs of a free society. We bark, we bite, we protect democracy and the public right to know. That’s our duty. ワンワン.

If you’re a lapdog for the powers that be, like executives at Fox News or News Corporation, journalism may be a rewarding and easy job.

Being a free-lance foreign correspondent and investigative reporter in Japan these days is a lot like being the private detective in the Dashiell Hammett novel, Red Harvest. You’re working for a newspaper editor who’s dead before you ever get to meet him (sounds like the newspaper business in general) and you have to struggle to get paid the money owed to you. You deal with gangs and thugs and crooked politicians, pitting them against each other, appearing to take work from anyone and at the end of the day, if you’ve brought someone to justice and you’re the last man standing: you’ve won. Collect your cash and go home.

Actually, it’s not really like much like that at all, but I wanted to start this article with a hard-boiled simile.

Jokes aside, making a living as freelance reporter in Japan these days is rewarding, but risky and unstable, and there are fewer and fewer of us doing it full time.

There are a lot of reasons for that. The number of working journalists is decreasing every year, while the number of people working in public relations keeps going up. Newspapers and magazines that have bureaus in Japan or that will pay for stories from Japan keep declining in number. Time’s Tokyo Bureau closed years ago. Newsweek folded. Dow Jones culled a large number of senior reporters this year. Reuters hires and fires at a schizophrenic pace. Bloomberg downsized. CNN and CNBC are barely here. The Los Angeles Times bureau once existed but I can only barely remember it. It used to have an office in the Yomiuri Building,

To my delight from spring of 2015 until the fall of 2016, I was a special correspondent for the L.A. Times. Then the newspaper ran out of money. No more budget for Japan.

Well, if you read the expose from the L.A. Times Guild (the labor union formed this year) it may not even be that they ran out of money – but rather that TRONC, Inc., the corporation running the newspaper into the ground, just sucks up all the profits and awards them to its executives, not the reporters. It certainly doesn’t spend more than it has to on paying for actual reporting. The problems at the Los Angeles Times are a microcosm of what’s happening all over the media – fewer and fewer people are asked to do more work with fewer resources. That’s the case for regular employees.

I applaud the union for actually standing up for members’ rights as workers and against mismanagement.

Maybe they’ll accomplish something.

Maybe some rich philanthropist will buy the newspaper as Jeff Bezos of Amazon did with the Washington Post, and restore it to glory.

And maybe I’ll do that job again if that happens. It was a great gig.

Mark that word, gig. Martin Fackler, who tried freelancing for a while but has now returned to the New York Times, says the experience taught him that “Freelancers are the Uber drivers of the new journalism gig economy. Everything is on a transactional basis, with no benefits or guarantees. You get more freedom, but pay for it with lower living standards and no job stability – like the rest of the gig economy.”

I’ve been a journalist since 1993–in Japan. Next year, I’ll have been doing it 25 years, a quarter of a century, more than half my life. At 48, I have now been a journalist half my life.

Half of those years (12.5, to be exact) were spent working as a regular employee at the world’s largest newspaper. I was a reporter and a regular employee for life aka (seishain/正社員), with the promise of a pension, all my insurance covered, paid vacation with use of the company’s corporate vacation facilities, an actual expense account, a bonus twice a year and a stable income. Sure, I worked 80-hour weeks but I didn’t have time to think about the work-life balance because there was none. Life was work and since I liked the work – investigating, interviewing, writing – it worked for me.

I’ve been working freelance since 2006. I’d like to say that it has gotten easier but in fact, even as you become well known, or relatively well known, life doesn’t get any easier. The joy of freelance work is that you can to some extent pick and choose the stories you want to write and who you write them for. The sadness of freelance work is that income is so unpredictable that you can’t really walk away from a gig and you have to pay constant attention to the news for a story that someone might want because it’s timely.

I currently write regularly for the Japan Times, ZAITEN, the Daily Beast and Forbes. I write for other publications as well but those are my main gigs. And I’m happy to have them.

However, to make my rent, I have to write a lot and I do part-time jobs. I do consulting work. I appear on Japanese television shows. I write short books and I write long books. I run a blog. I am constantly hustling.

Every day, I spend an hour or more reading newspapers and magazines in Japanese, looking for what may be a good story. I scan the articles and put them in a file. I make appointments and send out letters requesting interviews for the stories that I think are interesting. I answer email. I meet people in the afternoon, or attend press conferences. In the evening, I try to meet up with sources and maintain those relationships. I don’t have an expense account, so cheap bars and izakaya I like. If it’s an expensive place, I eat cheap somewhere first and then just have drinks.

You don’t have job security as freelancer and sometimes you don’t even get respect.

At least in Japan, you can get public health insurance, at an affordable rate. It’s one reason I can’t afford to leave Japan. That is a great perk of being a freelancer here.

By the way, the term for non-regular correspondents in the industry is “stringer.” It makes you sound sort of like a barnacle.

Below the stringer is “the fixer.” Fixers set up the meetings for the reporters coming to Tokyo, often doing the interpreting and translation of the materials. They are often not even credited for their work.

I rarely do fixing for anyone but I will for one public radio station because their correspondent is great; she credits me for the work I do on a story. That’s nice.

I’m not alone in struggling with the freelance life. Willie Pesek, author of Japanization: What the World Can Learn from Japan’s Lost Decades and recipient of the Society of American Business Editors and Writers prize for commentary also joined the freelance ranks this year. What he has to say is worth hearing:

Six months into my freelance existence, the very first of my career, I’m struck by George Orwell’s observation: “The choice for mankind lies between freedom and happiness and for the great bulk of mankind, happiness is better.” Having a full-time journalism gig strikes me as a similar tradeoff. The certainty of a reliable paycheck, medical benefits and access to an HR department has its merits. But the liberty freelancing affords – who you write for, which topics, which arguments -– is its own joy after two decades with major news companies.

But the biggest pros of this existence -– like working when I want to -– can also be key drawbacks. The main challenge, I’m finding, is maintaining a reasonable life/work balance. At times, while juggling various writing assignments, my inclination is to work around the clock. Creating boundaries -– like closing the laptop and having a life –- is a work in progress for me. So is knowing when to say “when.” Quality and actually has never been more important in this Orwellian fake-new world, but the quantity imperative gets in the way. Part of the tension, of course, relates to making a living –- one’s natural reluctance to turn down writing assignments. Finding a balance is something all freelancers will struggle with more and more in the years ahead. It’s a fact of this trade that quality comes first.

Then there’s the Tokyo problem. In my 15 years in Asia, I’ve always been a regional writer, which is proving to be an asset as a freelance. Lots of demand for columns for China, India, North Korea, the Philippines. Japan, not so much. Sadly, many overseas editors favor “weird Japan” items over, say, reality checks on Abenomics. But, hey, Tokyo is still a great, great city in which to live. The domestic story here, though, can be a hard sell. The Abe government using this latest electoral mandate to make big things happen would be the gift that keeps on giving for freelancers.

Willie, has a good point. Japan isn’t as important as it used to be.

I kind of wish sometimes that I hadn’t focused so much on Japan. But I’m okay with that. In the end, I may be working more hours now than I did as a regular employee. And as any freelancer will tell you, you also have to spend a lot of time on social media, getting people to read your articles, responding to those who have read them. Now and then you have to munch on the trolls who plague anyone who writes about Japan in a critical way.

Sometimes, people close to me ask me why I don’t change jobs. Here’s the best answer I can give.

Japan is my home. I love Japan. My children are Japanese. Most of my friends live here. Many Japanese people here are hard-working, honest and polite.

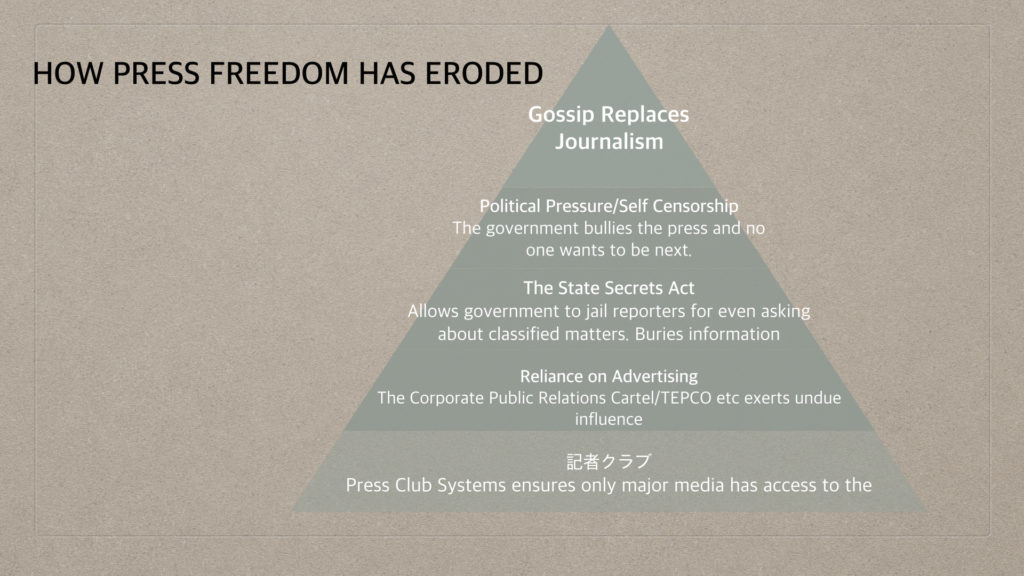

That doesn’t mean the society doesn’t have problems, such as child poverty, gender inequality and discrimination against: the handicapped, women, foreigners, especially Korean Japanese. Japan has a pestilent well-entrenched mob. There are nuclear dangers, staggering injustice in the legal system, repression of the free press, sexual assault on women with impunity for many assailants, rampant labor exploitation, death by overwork, and political corruption. Ignoring the problems doesn’t make them better. If you are offended by that, rethink your love of Japan.

I believe that journalism, especially investigative journalism, is a force for good and for maintaining a healthy society. It’s a vocation, not just a job. Sure some of the work is crappy, including writing about a series of crap-themed kanji instructional books for children—but you also get to do some enormous good.

Weird as it sounds, this year I took the vows to become a Zen Buddhist priest and I am one now. Not full-time.

It’s not easy being an investigative journalist and keeping the Ten Grave Precepts of a Soto Buddhist priest but there is a point where the two professions match up.

To paraphrase the Hokukyo, this is what we do.

Conquer anger with compassion.

Conquer evil with goodness.

Conquer trolls with humor and sarcasm.

Conquer ignorance with knowledge.

Conquer stinginess with generosity.

Conquer lies with truth.

The monetary rewards are not so great. Sometimes, the spiritual rewards make it seem like the best job in the world.

This was originally published in The Number One Shimbun, the periodical of The Foreign Correspondent’s Club of Japan. It has been slightly modified for New Years.